These men put off doctor’s visits again and again. Then came a tipping point

In an NHS survey, 48% of men said they felt pressure to “tough it out” when it came to potential health issues.

BBC News

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTwo years ago, Dan Somers started to experience a series of strange and unexplained symptoms. He had severe chest pain, was unable to keep food or even water down and kept “chucking up bile”.

Though he had a sense that something might be wrong, Dan was reluctant to seek medical help. “I’m really stubborn when it comes down to going to the doctors,” the 43-year-old from Ipswich tells the BBC. “I didn’t want to be a burden.”

Dan’s pain continued to get worse, until he was “near enough screaming on the floor in pain” and had to take time off work. It was the worst pain he’s ever experienced, he says upon reflection.

But “I honestly thought I could try and fix it,” Dan recalls.

It was his wife who finally managed to push Dan to see the doctor.

His GP sent him straight to hospital, where he was diagnosed with a gallbladder infection and spent a week recovering. He was told he had been close to getting sepsis.

Dan’s story mirrors those of other men who’ve told the BBC they’ve also put off seeking medical treatment – often until their symptoms became unbearable or until a loved one pushed them to get help.

Dan Somers

Dan SomersIt’s well known that men go to the doctors less than women, and data backs this up.

The NHS told the BBC it doesn’t release demographic data about GP appointments. But according to the ONS Health Insight Survey from February, commissioned by NHS England, 45.8% of women compared to just 33.5% of men had attempted to make contact with their GP practice for themselves or someone else in their household in the last 28 days.

Men were more likely to say they weren’t registered at a dental practice and “rarely or never” used a pharmacy, too.

They also make up considerably fewer hospital outpatient appointments than women, even when pregnancy-related appointments are discounted.

Men are “less likely to attend routine appointments and more likely to delay help-seeking until symptoms interfere with daily function,” says Paul Galdas, professor of men’s health at the University of York.

This all affects men’s health outcomes.

Experts say there’s a long list of reasons why men might put off seeking medical help, and new survey data from the NHS suggests that concerns about how they are perceived come into play.

In the survey, 48% of male respondents agreed they felt a degree of pressure to “tough it out” when it came to potential health issues, while a third agreed they felt talking about potential health concerns might make others see them as weak. The poll heard from almost 1,000 men in England in November and December 2024.

Society associates masculinity with traits like self-reliance, independence and not showing vulnerability, says social psychologist Prof Brendan Gough of Leeds Beckett University. “Men are traditionally supposed to sort things out themselves”.

“It’s worrying to see just how many men still feel unable to talk about their health concerns,” says Dr Claire Fuller, NHS medical director for primary care. She notes that men can be reluctant to seek medical support for mental health and for changes in their bodies that could be signs of cancer.

“GPs are often the best way to access the help they need,” she adds.

‘Men are inherent problem-solvers’

Kevin McMullan says he’s learned from working for men’s mental health charity ManHealth that men want to solve their own problems. He says he struggled with his mental health for years before he finally got help.

“You want to fix it yourself. Men are inherent problem-solvers and how you are feeling is a problem in the same way that having a flat tyre is a problem,” says Kevin, 44, from Sedgefield in County Durham.

This is something that the Health Insights Survey indicates, too. The data suggests that when people were unable to contact their GP practice, men were significantly more likely than women to report “self-managing” their condition, while women were more likely than men to go to a pharmacy or call 111.

“Many men feel that help-seeking threatens their sense of independence or competence,” Prof Galdas says.

Kevin McMullan

Kevin McMullanProf Galdas points to other factors deterring men from going to the doctors, like appointment systems that don’t fit around their working patterns.

Services also rely on talking openly about problems, he suggests, which doesn’t reflect how men speak about health concerns – and there are no fixed check-ups targeting younger men.

Women, in contrast, are “sort of forced to engage in the health system” because they might seek appointments related to menstruation, contraception, cervical screenings or pregnancy, says Seb Pillon, a GP in Bolton.

And they’re largely in control of organising their family’s healthcare, too. For example, roughly 90% of the people who contacted the children’s sleep charity Sleep Action for help in the last six months were mums, grandmothers and other women in the children’s lives, its head of service Alyson O’Brien says.

Because women are more integrated in the healthcare system – through seeking support for both themselves and their children – they’re more health-literate and are often the driving force behind their partners seeking medical help, according to Prof Galdas.

And men just have a different attitude towards healthcare, Dr Pillon says. He believes many see it solely as treatment – solving their problems – rather than preventative. Men are, for example, less likely to take part in the NHS’s bowel cancer screening programme. As Prof Galdas says: “men often seek help when symptoms disrupt their ability to function.”

‘Massive waste of time’

For Jonathan Anstee, 54, from Surrey, it took his symptoms getting drastically worse for him to book a doctors appointment, after months of stomach aches and blood in his stool.

“The pain got a lot worse and the blood got a lot worse,” Jonathan says. “But even when I went to the doctors, I was sat in the waiting room thinking ‘this is a massive waste of time’.”

Jonathan Anstee

Jonathan AnsteeHe was diagnosed with bowel cancer in September 2022.

Throughout his life he’d generally avoided doctors appointments, Jonathan says. And as a father, “you’re used to worrying about your kids and not yourself,” he says. Going to the doctors for himself, not his children, seemed “a bit sort of indulgent”, he says.

Last year, Jonathan was told his bowel cancer was stage four.

Having blood in his stool had felt too embarrassing to talk to his friends and family about at the time. Jonathan’s advice to other men is: “There is absolutely no need to be embarrassed. The alternative could kill you – literally.”

‘Connection can make a big difference’

In recent years, support groups for men with cancer and mental health conditions have sprung up.

Matthew Wiltshire started the men’s charity the Cancer Club after being diagnosed with bowel cancer in 2015. He died in 2023.

Matthew felt there wasn’t a space “where men were openly talking about what it’s like to go through cancer,” his son, Oliver Wiltshire, says. “He also noticed how much of the emotional load was being carried by the women around him.”

Through the Cancer Club, men can message online and attend sports events together.

“Whether it’s practical advice, honest chat or just knowing someone else gets it, that connection can make a big difference,” Oliver adds.

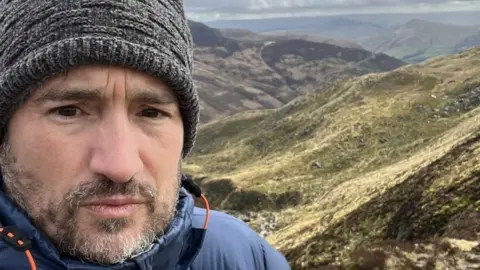

Paul Galdas

Paul GaldasExperts say that while men’s attitudes towards healthcare are gradually changing for the better, more work still needs to be done.

Prof Galdas believes men will engage more if services are redesigned to meet their needs – proactively offering support, having flexible access and focusing on practical action to improve mental health issues.

“There’s good evidence from gender-responsive programmes in mental health, cancer care, and health checks showing this consistently,” he says.

For Dr Pillon, it’s adding general health checks for men in their 20s to get them more used to accessing medical care.

They’re already available through the NHS for people aged 40 to 74, but introducing them for younger men who might not otherwise go to the doctors would “embed the idea that you can come and use health services”, he says.

If you have been affected by some of the issues raised in this story, information and support can be found at the BBC’s Action Line.