The Nasdaq Sell-Off Has Accelerated, and History Suggests It’ll Get Worse in the Coming Months

Over the last month, Wall Street has sent investors a stern but necessary reminder that stocks can indeed move lower just as easily as they can head higher.

In 2024, we’ve witnessed the mature stock-driven Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJINDICES: ^DJI), benchmark S&P 500 (SNPINDEX: ^GSPC), and innovation-fueled Nasdaq Composite (NASDAQINDEX: ^IXIC) all fly to record-closing highs on multiple occasions. This is consistent with what history has shown us. In other words, Wall Street’s prominent stock indexes increase in value over long periods, eventually putting corrections, bear markets, and crashes in the rearview mirror.

However, history is a two-sided coin.

Among Wall Street’s three major stock indexes, the growth stock-powered Nasdaq has been hit the hardest. Over a three-session stretch from Aug. 1 through Aug. 5, the index most responsible for lifting the broader market to new heights suffered a 1,399-point decline. This included a 576-point tumble on Monday, Aug. 5, representing the eighth-largest nominal-point drop in the Nasdaq’s storied history.

Although most investors are probably wishing for a quick bounce from this accelerating Nasdaq sell-off, history suggests an even steeper decline is yet to come.

A historic overvaluation of equities primes the Nasdaq for significant downside

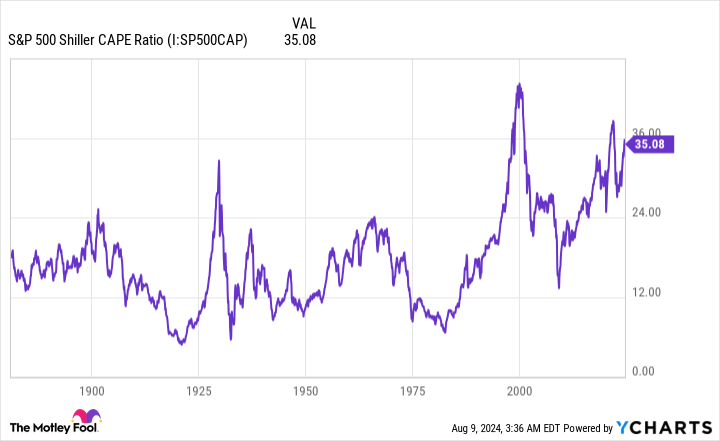

While history doesn’t repeat itself to a T on Wall Street, it does tend to rhyme. One indicator that strongly suggests the sell-off we’re witnessing in the Nasdaq Composite is just getting started is the valuation-based Shiller price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, which is also commonly referred to as the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio, or CAPE ratio.

The traditional P/E ratio, which divides a company’s share price into its trailing-12-month earnings per share, is the most popular valuation tool investors have at their disposal. By comparison, the S&P 500’s Shiller P/E is based on average inflation-adjusted earnings from the prior decade. Looking at 10 years’ worth of earnings history, as opposed to one, helps to smooth out major events (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) that can adversely impact traditional valuation models.

When the closing bell tolled on Aug. 8, the S&P 500’s Shiller P/E stood at 34.30, almost precisely double its average reading of 17.14 when back-tested to 1871.

Since the mid-1990s, it’s not been uncommon for the Shiller P/E to be above its historic average. The advent of the internet made accessing information easier than ever for investors. Further, periods of historically low interest rates fueled risk-taking, which led to multiple expansions.

However, instances wherein the S&P 500’s Shiller P/E crosses above 30 during a bull market have historically signaled trouble. Dating back to January 1871, there have been only six such occasions, including the present. Following each of the five prior instances, the Dow Jones, S&P 500, and/or Nasdaq Composite tumbled by 20% to 89%. In other words, premium valuations are only tolerated for so long on Wall Street.

Be aware that the Shiller P/E isn’t a timing tool, and valuations can remain extended for weeks, months, or even years, as they did prior to the bursting of the dot-com bubble.

But based on what history has shown, modern-era Shiller P/E readings north of 30 have eventually retraced to around 22, give or take a bit in each direction. This implies the S&P 500 could lose in the neighborhood of a third of its value, with the Nasdaq Composite likely being hit even harder.

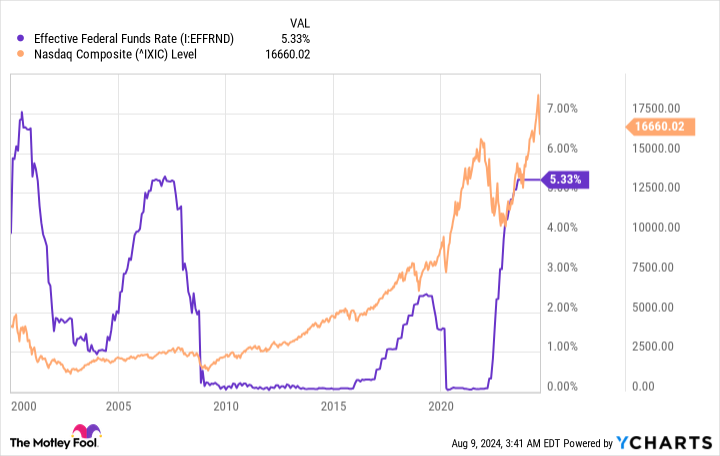

A shift in monetary policy is an ominous sign for Wall Street

While it’s not a metric, per se, like the Shiller P/E ratio, Federal Reserve monetary policy does tend to be historically relevant to Wall Street.

On the surface, you’d likely think a rising-rate environment would be bad for equities, while a rate-easing cycle would be great news. Interestingly, though, this couldn’t be further from the truth for stocks.

Typically, when the Federal Open Market Committee increases its federal funds rate, it does so to keep the U.S. economy from overheating. In other words, tightening cycles are usually undertaken when the U.S. economy is in great shape.

On the other hand, rate-easing cycles typically kick off when something isn’t right with the U.S. economy or some adverse event has taken place. Although the prospect of cheaper lending rates will eventually spur borrowing among consumers and businesses, it can take more than a year for these effects to really be felt throughout the economy.

Since this century began, the start of rate-easing cycles has been a harbinger of bad news for stocks:

-

On Jan. 3, 2001, with the dot-com bubble bursting, the Fed began a rate-reduction cycle that lowered the federal funds rate from 6.5% to 1.75% in less than a year. However, it took 645 calendar days following this initial rate reduction before the stock market found its bottom.

-

On Sept. 18, 2007, with the financial crisis taking hold, the Fed began a rate-easing cycle that lowered the federal funds target rate from 5.25% to a range of 0%-0.25%. What’s noteworthy is that stocks didn’t bottom out until 538 calendar days later.

-

This century’s third and final rate-easing cycle began on July 31, 2019, with the federal funds rate ultimately returning to its 0%-0.25% range. The stock market bottomed out 236 calendar days after this initial cut during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

On average, since 2000, it’s taken 473 calendar days, or more than 15 months, for the stock market to bottom out following an initial rate cut. With the nation’s central bank expected to kick off a rate-easing cycle in September, history would suggest that trouble awaits the Nasdaq Composite and stocks in general.

History especially favors investors with a long-term horizon

Though I made clear earlier that history is a two-sided coin, it’s just as important to recognize that boom-and-bust cycles for the U.S. economy and stock market aren’t linear. If you have a choice between being an optimist or pessimist, history favors being positive — especially if you have a long-term mindset.

For example, history shows us that economic expansions and contractions aren’t mirror images of one another. While there have been 12 U.S. recessions since the end of World War II, only three reached the 12-month mark, and none surpassed 18 months. Meanwhile, two periods of economic growth topped 10 years. The U.S. economy spends a disproportionate amount of time growing, which logically suggests that corporate America will see sales and profits rise over the long run, too.

Even though the stock market and the U.S. economy move independently of one another, we see these same nonlinear advances and declines translate to Wall Street.

Last year, the researchers at Bespoke Investment Group released the data set you see above, which compared the average length of bear and bull markets in the S&P 500 since the start of the Great Depression in September 1929. All told, 27 separate bear and bull markets were analyzed.

What this data set showed is that the average bear market for the S&P 500 has lasted just 286 calendar days, or roughly 9.5 months. Comparatively, the typical S&P 500 bull market has hung around for 3.5 times as long (1,011 calendar days). You’ll also note that 13 of the 27 bull markets have lasted longer than the lengthiest bear market.

While history is quite clear in suggesting that the Nasdaq Composite and stocks, in general, could head meaningfully lower in the months to come, this forecast decline would represent yet another in a series of opportunities for long-term investors to buy stakes in high-quality businesses at advantageous prices. Maintaining perspective while being mindful of history can be highly profitable for patient investors.

Don’t miss this second chance at a potentially lucrative opportunity

Ever feel like you missed the boat in buying the most successful stocks? Then you’ll want to hear this.

On rare occasions, our expert team of analysts issues a “Double Down” stock recommendation for companies that they think are about to pop. If you’re worried you’ve already missed your chance to invest, now is the best time to buy before it’s too late. And the numbers speak for themselves:

-

Amazon: if you invested $1,000 when we doubled down in 2010, you’d have $18,802!*

-

Apple: if you invested $1,000 when we doubled down in 2008, you’d have $40,860!*

-

Netflix: if you invested $1,000 when we doubled down in 2004, you’d have $341,878!*

Right now, we’re issuing “Double Down” alerts for three incredible companies, and there may not be another chance like this anytime soon.

*Stock Advisor returns as of August 6, 2024

Sean Williams has no position in any of the stocks mentioned. The Motley Fool has no position in any of the stocks mentioned. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.

The Nasdaq Sell-Off Has Accelerated, and History Suggests It’ll Get Worse in the Coming Months was originally published by The Motley Fool