Thailand, the “Detroit of Southeast Asia” is at the forefront of China’s battle for the global auto market

China has invested at least $1.4 billion in the nearby country’s auto plants.

Narong Yuenyonghattaporn, a retired civil servant in Bangkok, bought an electric car made by GAC Aion earlier this year. He’s part of a growing number of Thai drivers buying EVs sold by Chinese car companies but made in Thailand, a nation that’s become one of the front lines in the global battle for auto-market supremacy.

In the past two years, Chinese automakers including BYD, GAC Aion, and Chery have announced plans to build manufacturing facilities in Thailand. BYD’s and GAC Aion’s factories started operations in July, and so far Chinese investments in Thai auto plants total at least $1.4 billion.

Narong’s EV is one of the 80,000 battery-electric vehicles the Electric Vehicle Association of Thailand is projecting will be registered this year. Last year, Thailand registered 76,739 BEVs, according to government data, 6.5 times the number in 2022.

Though the pace of EV adoption in Thailand slowed this year, as in many other parts of the world, it’s part of a growing trend. Chinese car companies, led by BYD, are breaking into markets long dominated by automakers from Japan, the U.S., and Germany. Since around 2020, Chinese auto brands, especially EV manufacturers, have been expanding internationally in search of more revenue as fierce competition and oversupply at home eat into their market share.

But with geopolitical barriers impeding the pursuit of car buyers in Europe and North America, these Chinese automakers are aggressively entering middle-income markets like Thailand, Indonesia, Brazil, Malaysia, and Argentina, where there are often no domestic auto champions to protect, and governments have at least a somewhat cordial relationship with Beijing.

In Thailand, Chinese EV manufacturers are starting to challenge Japanese brands that have long dominated the Thai auto market. Chinese brands have bought up huge billboards on highways between Suvarnabhumi Airport and Bangkok. In the city, more showrooms now feature vehicles from China, while Chinese EV production facilities are a little less than a two-hour drive away from Bangkok. Once fully operational, these Chinese EV facilities could together ramp up production to build at least 320,000 vehicles a year.

“There’s a couple of things that make Thailand attractive,” says Eugene Hsiao, the Hong Kong–based head of China equity strategy and China autos at Macquarie. “The first and most obvious is that Thailand as a country is relatively friendly to China. I think that’s very important. The second is that the auto supply chain is already fairly well developed. That was pretty much done by the Japanese historically.”

Thailand’s central location in the region makes the country a gateway to the wider Southeast Asia market, and Thailand itself has a big domestic automotive market compared to the rest of the region, said a GAC Aion Thailand spokesperson.

As they have in Thailand, Chinese auto manufacturers are making investments around the globe. Led by established brands like BYD, SAIC, and Chery, they are assembling cars in-country either to gain incentives or avoid tariffs.

“Affordability is a universal value proposition.”

Bill Russo, Founder and CEO, Automobility

While Brazil has reinstated import taxes on electric vehicles regardless of origin, the government also has a program that incentivizes companies to decarbonize, and auto companies can qualify for tax rebates based on the energy efficiency of the car models and the density of local production. Manufacturing in Hungary could potentially allow Chinese EVs to bypass EU tariffs, and in Malaysia, despite having local auto brands, the government provides tax exemptions for locally assembled EVs.

There is a clear strategy behind the choice of nations where Chinese manufacturers have set up shop, says Hsiao. In this case, bigger doesn’t necessarily mean better.

“The best markets in terms of GDP per capita would be the big developed markets, meaning the U.S., Europe, and Japan. Those markets are the most closed, you could argue,” he says—yet there are “other markets that are smaller but meaningful” for Chinese auto brands.

Beijing identified the EV sector as a strategic emerging industry worthy of state support more than a decade ago, handing out subsidies to both manufacturers and consumers. There were as many as 500 EV companies in China at one point, but competition and a gradual phasing out of subsidies has driven consolidation.

Traditional automakers from Europe and the U.S. are struggling to compete with or match Chinese EV offerings at lower price points. That has eaten into their bottom line, with Volkswagen in late October announcing plans to cut pay and close factories. Japanese automakers have also been slower to transition toward electric vehicles, and Japan’s biggest automaker, Toyota, thinks the EV transition won’t happen as quickly as anticipated, placing its bet on hybrids. That strategy seems to be working for Toyota so far, as it retained its title as the world’s largest automaker last year. Data from Toyota for the first nine months of this year showed Toyota sold almost 3 million hybrid vehicles, a 19.8% year-on-year increase.

Auto Manufacturing makes up 10% of Thailand’s GDP and contributes about 850,000 jobs, according to the International Labour Organization. Its history with carmaking dates to the 1960s, when Japanese makers like Toyota, Nissan, and Mitsubishi opened up production facilities in the country. Not long after, American and European brands followed.

From the beginning, Thailand relied heavily on incentives and tariffs to turn itself into a regional auto-manufacturing hub. It started an import-substitution policy—replacing foreign imports with domestic production—for the automotive industry in the 1960s, attracting foreign automakers to set up production facilities in the country.

Thailand’s trade agreement with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN, also means automakers enjoy lower export duties when selling within the region. The Thai government’s high import tax of up to 80% for passenger vehicles and 30% for pickups further incentivizes automakers to keep producing in Thailand.

Now the Thai government is betting EVs will allow it to maintain its position as “the Detroit of Southeast Asia.”

Bangkok has a “30@30” plan, with a goal of 30% of autos produced to be EVs by 2030. In early 2022, Thailand approved a package of incentives to promote EV adoption in the country, with the aim of eventually making Thailand a regional EV-manufacturing hub.

Tangible investments in manufacturing from Chinese companies can affect the decision-making of buyers like Narong, the retired civil servant. Because these companies have set up assembly plants in Thailand, parts are more readily available and maintenance should be easier, helping reassure him of Chinese cars’ reliability. A less fractious geopolitical relationship, too, may cause buyers like him to be more open to giving Chinese cars a chance.

“They also produce a lot of electric vehicles to serve their own market, and their government gives full endorsement, and I believe these result in good experiences and reliability,” Narong says.

But while these Chinese EVs are starting to make inroads in Thailand, they are still the challengers and have not overtaken the incumbent carmakers yet. Charging anxiety remains an issue that needs to be addressed, and for the most part, EV adoption is happening faster in Bangkok. In mountainous regions like Chiang Mai, a Toyota pickup may continue to be the favored choice.

Toyota was still the No. 1 car company in Thailand last year with 265,949 vehicles sold, according to data from its Thai subsidiary, trailed by Isuzu, Honda, and Ford. BYD was sixth with 30,432 cars sold, just 2,000 vehicles shy of fifth-place Mitsubishi. Collectively, Chinese brands, led by BYD, accounted for 11% of the new-auto market share, more than double the year before, while sales of Japanese vehicles declined. Chinese brands accounted for some 80% of EV sales in Thailand last year.

Thailand’s tax rebates for EVs make the country an attractive market, says GAC Aion Thailand’s spokesperson. Other nations are also offering tax rebates for EVs, which should further drive demand.

“Affordability is a universal value proposition,” says Bill Russo, the founder and CEO of Automobility, a Shanghai-based strategy and investment advisory firm for the automotive industry.

Yet, Russo argues, the threat of Chinese car manufacturers to established automakers is about more than just EVs.

Despite the talk about Chinese EVs breaking into overseas markets, China is also exporting huge numbers of conventional internalcombustion-engine (ICE) vehicles, he says. Russo explains that because consumers in China, the world’s largest auto market, are rapidly choosing EVs over ICEs, the country’s automakers are left with more ICE vehicles than the market can absorb. That means they are looking to unload millions of cars elsewhere. While China hasn’t had much success selling gasoline powered cars in Thailand, other markets still on the fence about EVs are ripe for them.

“Sell them to Russia, sell them to Mexico, sell them to Brazil. Sell them to wherever consumers are not trusting EVs yet,” Russo says.

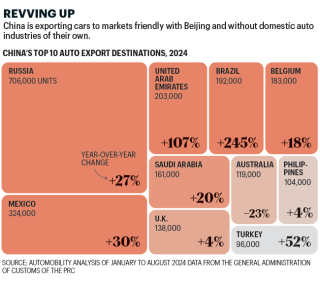

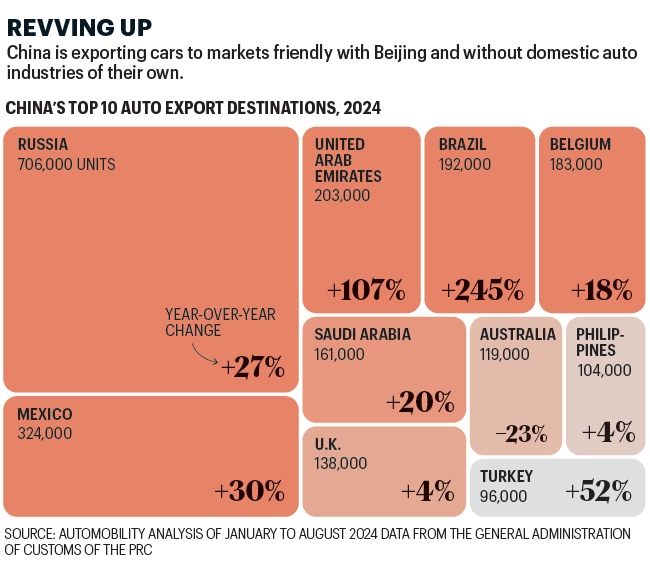

China exported 4.91 million vehicles last year and overtook Japan as the world’s largest auto exporter. Plug-in hybrids and battery-electric vehicles accounted for about 25% of the exports, which means Chinese brands are also selling plenty of gasoline vehicles.

Exports to Russia still dominate, but Chinese automakers have vastly expanded their market share in Mexico, Brazil, Turkey, and the UAE, according to data compiled by Automobility.

Governments are only looking at Chinese carmakers through an EV lens, so ICE vehicles are still being exported without as many barriers, Russo says. That gives Chinese automakers an opening.

“You set up your dealer networks, you establish your brand, you’ve got that beachhead,” Russo says. Once entrenched as trusted brands, carmakers can begin introducing EVs.

The automakers employed the same strategy in China, Russo says: “That’s exactly what they’re going to do internationally; they’re going to go into every country that they can and then pivot over to EVs.”

This article appears in the December 2024/January 2025 issue of Fortune with the headline “Changing Lanes.”