More money and staff – so why isn’t the NHS more productive?

Labour has launched an investigation into what’s wrong with the NHS. Is productivity the place to start?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe new government has made tackling NHS waiting times a key priority – and this week appointed NHS surgeon and former health minister Lord Ara Darzi to investigate what is going wrong. Is productivity the place to start?

The scale of the challenge facing Health Secretary Wes Streeting was made clear as he announced the review on Thursday. The latest performance figures – the first published since the election – showed the hospital backlog had risen again for a second month in a row, hitting 7.6 million. The British Medical Association called it a “shameful” legacy for the Tories to leave.

In its manifesto, Labour insisted it had a plan to tackle this – creating an extra 40,000 appointments and operations a month, by getting the NHS to do more at weekends as well as using the private sector more.

It has pointed to hospitals in London and Leeds that have had great success in doing weekend working, which has allowed them to improve efficiency through high-intensity use of operating theatres. Surgeons carry out the operations across two theatres with one being used to operate on the patient, while the next patient is readied in the other.

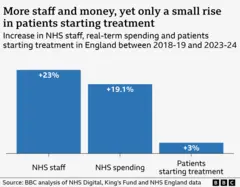

But these are the exceptions. If you look across the entire NHS, hospitals have actually struggled to increase activity despite more money being invested and more staff being employed. Compared to five years ago, spending after inflation has risen by nearly a fifth and the workforce by nearly a quarter, yet the number of patients starting treatment for things such as knee and hip replacements, has barely increased.

The strikes by junior doctors and other staff seen over the past year have had an impact. NHS England estimates that during 2023-24, 350,000 more treatments would have been started if there had been no industrial action. But even that leaves hospitals well short of what you would have expected, if treatments had gone up by as much as spending and staffing.

It is a similar picture if you look at all types of treatment, including follow-up checks and pre-treatment tests and scans, not just those starting their core treatment and therefore coming off the waiting list.

‘Return on investment terrible’

This productivity puzzle – as the Institute for Government (IfG) calls it – has been a cause of concern at the heart of government for some time.

During an election debate in front of health leaders last month, a candid Lord Bethell, who served as a health minister in the last government, said the Treasury had become “sick to death” of pouring money into the health service only to see productivity fail to improve: “They [the Treasury] believe the return on investment is terrible.”

But it is not just in the corridors of Westminster that the perception has developed. The public is also concerned, according to Anna Quigley, research director at Ipsos UK: “Generally around eight in 10 say they are willing to pay more tax to fund the NHS. But they also say it needs to make changes – cut out waste and inefficiency.”

The temptation is to assume it was the pandemic that threw a spanner in the works – after all it led to a dramatic fall in treatments being done, and the waiting list to balloon. Could it be that the NHS is still recovering from the shock of that?

The IfG analysis of the problem published last year suggests not.

Focusing on treatments is just one rather blunt mark of productivity, so the IfG looked at a range of different measures – and found the NHS actually started to become less productive in the late 2010s after about 15 years of improving productivity.

It was clear, the IfG concluded, the pandemic may have pulled the trigger, but the gun was loaded well before Covid struck.

The Nuffield Trust has come to a similar conclusion in an analysis published this week, pointing out the NHS has struggled more than other countries, such as Finland and Spain, to get waiting times down since the peak of the pandemic.

It’s director of research Sarah Scobie says the new government faces an “enormous uphill battle” to get the NHS back on track.

Crumbling buildings

So what’s causing the problems? In a system as complex as the NHS there will never be a single reason for something.

The lack of spending on buildings is a key factor, the IfG said.

As funding has been squeezed, the repair bill for the NHS estate has been creeping up and stands at £11.6bn – a rise of 13.6% on the previous year.

The consequence of this is that every year thousands of patients see their care disrupted because of incidents relating to infrastructure problems.

A BBC investigation earlier this year found problems including patients waiting for dialysis being sent home because of water supply issues, power being lost in operating theatres and sewage leaking into patient areas.

The lack of spending on buildings and equipment – known as capital spending – also means the NHS has one of the lowest number of scanners among rich nations, creating a bottleneck for tests to diagnose health problems. The lack of 21st century IT systems is another well-known problem.

The IfG also highlighted delayed discharges. This is when patients are medically fit to leave hospital but cannot, because of the lack of care in the community.

Every day around one in nine hospital beds is occupied by someone in this position.

“It’s clogging up the whole system,” says Sally Warren, director of policy at the King’s Fund think tank, who is now moving to the Department of Health and Social Care to oversee a new 10-year strategy for the government: “It’s a huge inefficiency.”

The staffing problem

Ms Warren, who spoke to the BBC before her appointment to government was confirmed, also highlights workforce factors as a problem, including high rates of sickness and low morale, as well as the increasing number of less experienced staff – something that often gets overlooked when staffing figures are discussed.

Research by the Nuffield Trust has shown that over the past five years the number of newly qualified nurses – those with less than a year’s experience – has nearly doubled as a proportion of the workforce, to one in 14.

“The NHS has lost a lot of its long-serving staff – and that hasn’t helped. There is some evidence that having a less experienced workforce leads to a more risk-averse approach,” says Ms Warren.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShe adds that this has several consequences, from keeping people in hospital too long to being too ready to admit them.

It is a point acknowledged by NHS England’s recent review of productivity, which accepted hospitals in particular had become less efficient.

That review also highlighted spending on agency staff to plug gaps caused by staff sickness and vacancies – while the number of staff being employed has gone up, one in 13 posts are still vacant.

It means an increasingly desperate NHS can find itself paying over-the-odds to get cover, with research showing some paying out up to £2,500 to fill nursing shifts.

Funding rises not all they seem

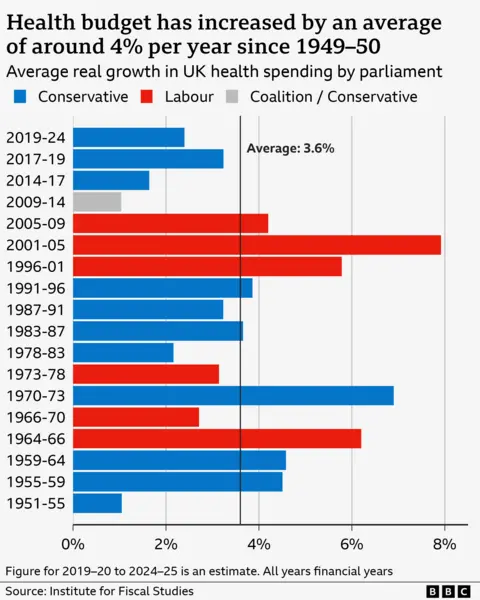

The money situation is also not as clear-cut as it would seem. While the NHS budget has gone up, the rises have not been as much as the NHS was traditionally used to.

Historically, the budget has increased by around 3-4% above inflation on average – a figure many experts see as necessary to keep pace with the ageing population and advances in medicine.

But during the 2010s it was limited to 1% to 2%. Over the last parliament it was higher, but still below the historical average.

One of the problems, says Ms Warren, is that was only because of the emergency bailouts that were given.

By their very nature, she says, they have tended to come “as late as humanly possible” and often in ring-fenced pots, which has not made for good financial decision-making: “You could improve the NHS with less if you had a settled three-year funding settlement.”

That’s something senior NHS leaders agree with whole-heartedly. Last year the final tranche of winter funding came in January – after the peak in pressures had hit.

“It was crazy,” one hospital chief executive told me. “We had just battled through some of the toughest weeks many of us had seen – we should have had the money months and months before. In theory, that should be fairly easy to resolve – the other problems holding us back aren’t.”