Inside the gym building champions – and community

Molly McCann and Paddy Pimblett are MMA superstars but their Liverpool gym focuses on fighters of all abilities

This article contains details of poor mental health and suicide. If you have been affected by any of the issues raised, BBC Action Line can provide contacts to find help.

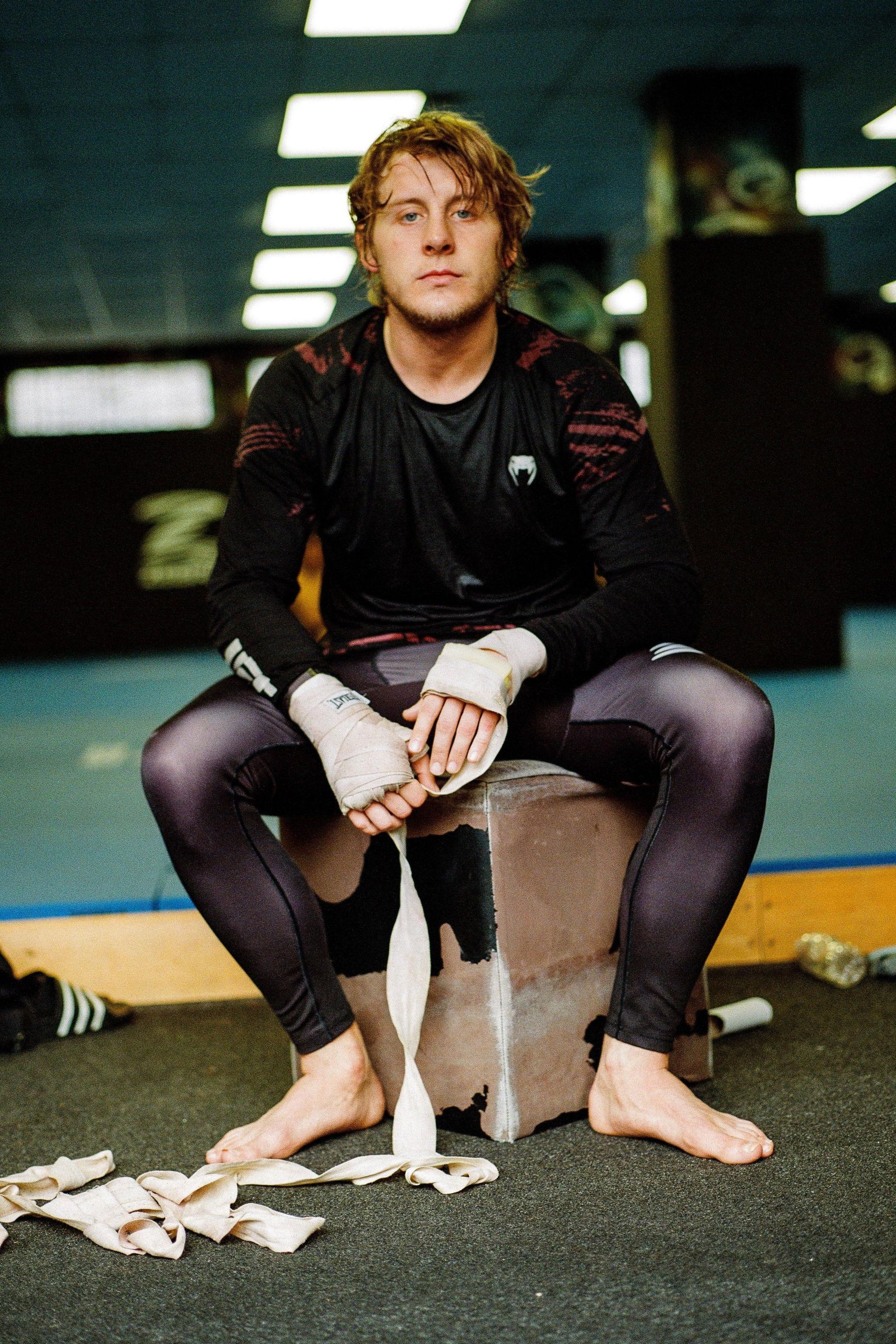

“I’ve got some proper Halloween scars on this one.”

MMA fighter Paddy ‘The Baddy’ Pimblett points to the marks left by three operations on his foot. He’s had another three on his hands.

“My body is falling apart at 29 – but I’ve been fighting since I was 15,” he says.

“I just get on with it.”

The Next Generation Gym is where he gets on with it.

Pimblett and Molly ‘Meatball’ McCann, 34, are the two highest-profile members of a tight-knit MMA fighting community at the renowned Liverpool gym.

It is where both are preparing for fights in Manchester later this month; contests which could be significant to their careers after 18 months of turbulence, headlines and life changes.

They are part of a wider, longer-term project though.

Their training is led by head coaches Paul Rimmer and Ellis Hampson, who joined forces 20 years ago to build an MMA community and a lasting legacy for Liverpool.

In 2001, a 21-year-old Rimmer, inspired by a childhood interest in karate and Japanese wrestling programmes, took out a £6,000 loan and left his office job. He travelled across the Atlantic to the Next Generation Fighting Academy in Irvine, California, 40 miles south east of Los Angeles.

He trained all day, every day, for nine months under the tutelage of Chris ‘The Westside Strangler’ Brennan.

“I slept on bunk beds in the back of the gym and walked to a weights gym to take showers,” he says.

“It was really hard.”

He came back with a Brazilian Jiu Jitsu black belt and a brand that he was determined to spread to Liverpool.

“Next Generation in Liverpool has been about putting the stuff in place that we never had here,” he says.

“There was no MMA, fighting heroes or gyms to look up to. This is an alternative to to offices and football to make opportunities for kids in this city.”

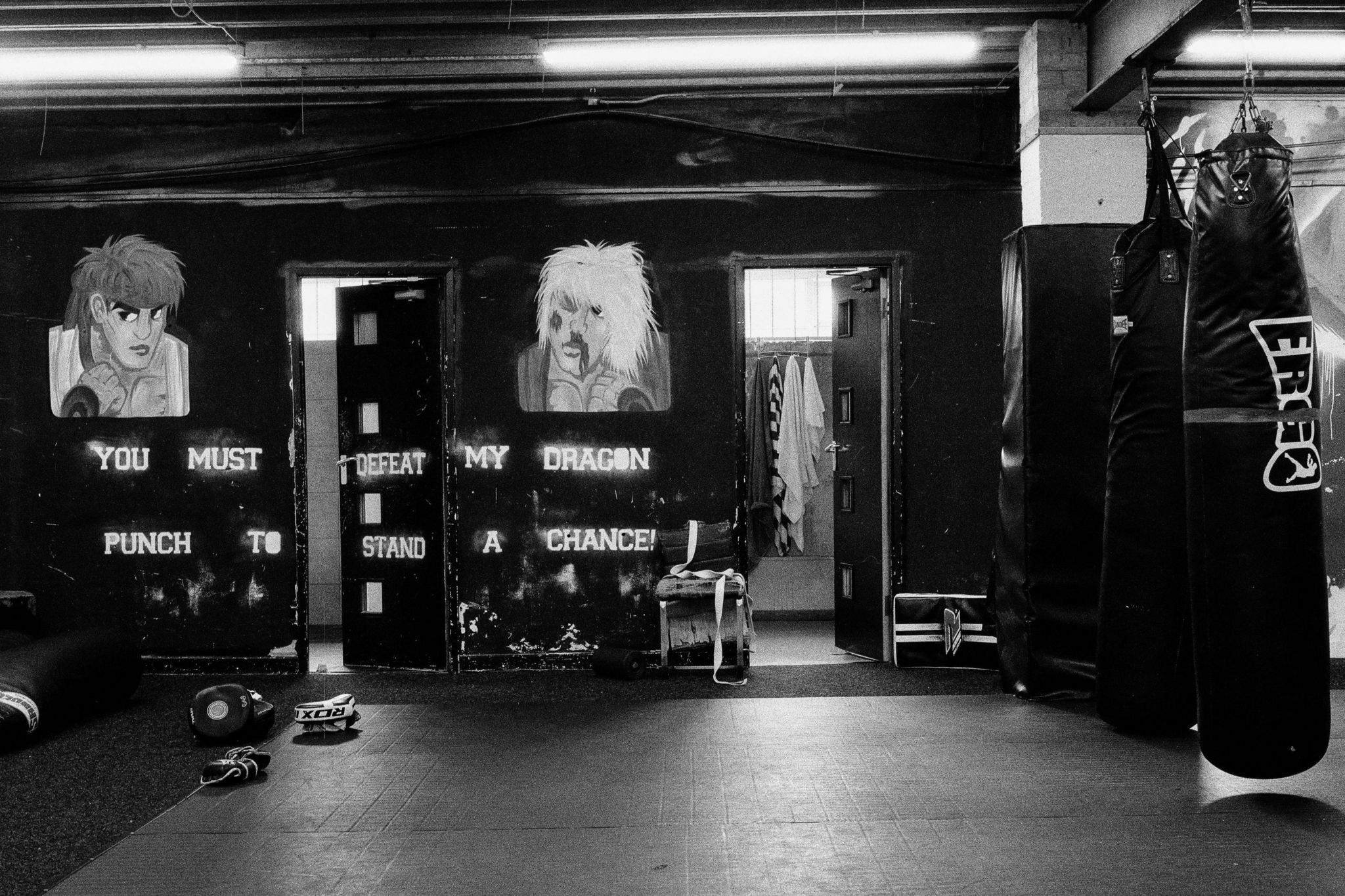

The gym is split across two floors in a windowless industrial building in the Fabric District, an area which holds the history of the Liverpool’s rag trade. Metal shutters are peeled back to reveal an expanse of bright blue training mats and interior walls covered in graffiti art.

The gym’s community comes from all walks of life, with under-16s training next to the likes of Pimblett and McCann.

In total, it is home to 15 professionals across four major MMA promotions – UFC, Bellator, Cage Warriors and Oktagon.

Two coaches are at the centre of it all, Hampson in full body pads while Rimmer sits on the floor watching intently and absorbing every detail.

The atmosphere is one of concentration and camaraderie, rather than tension or testosterone. The attention to detail you might even describe as geeky.

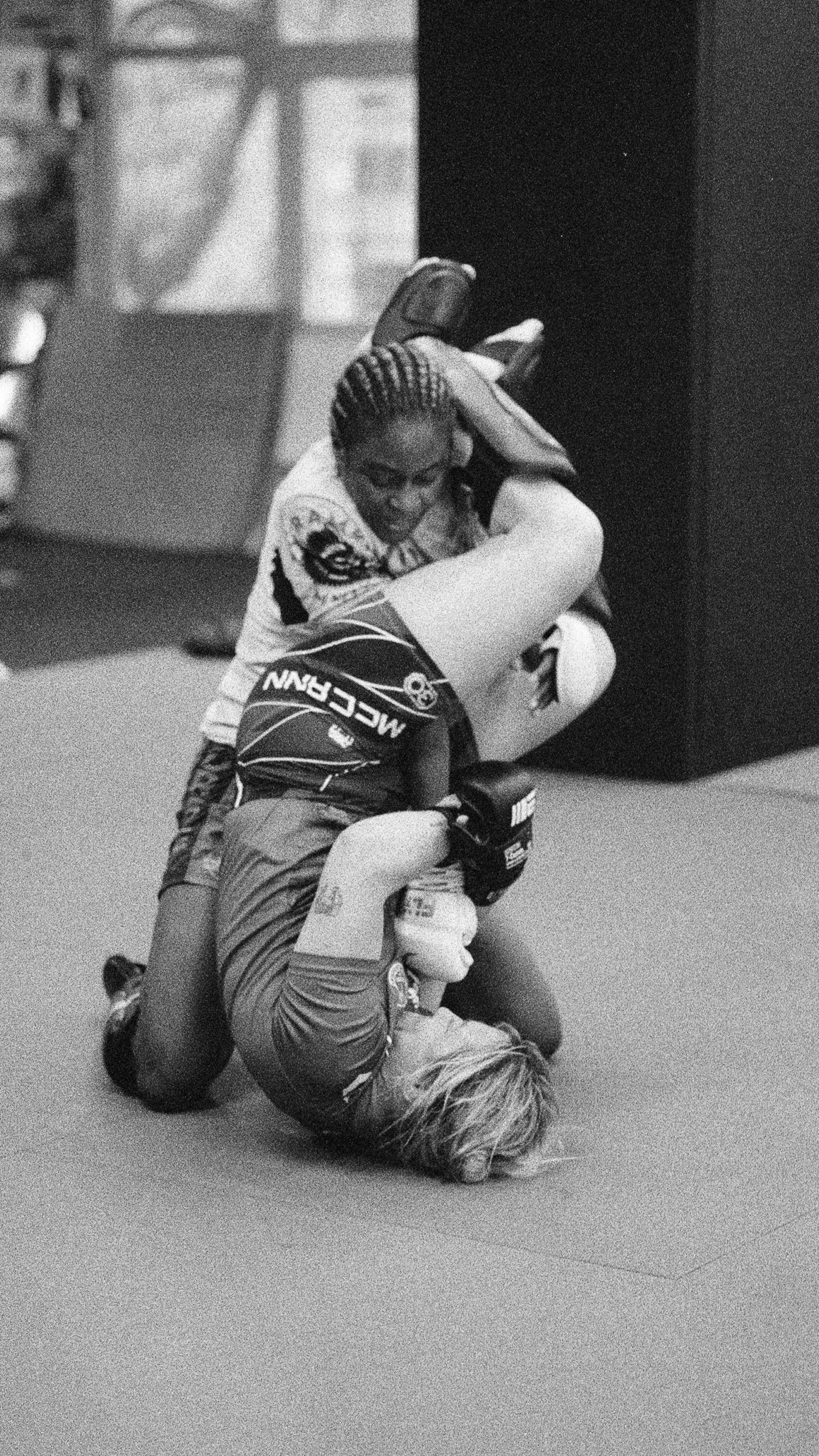

“Most of it is like a dance,” says McCann as we sit on the mats after a training session.

“If you look at combat sports or martial arts, it’s an art form. It’s not plain sailing, it’s so hard, but for me it’s the truest form of expression.”

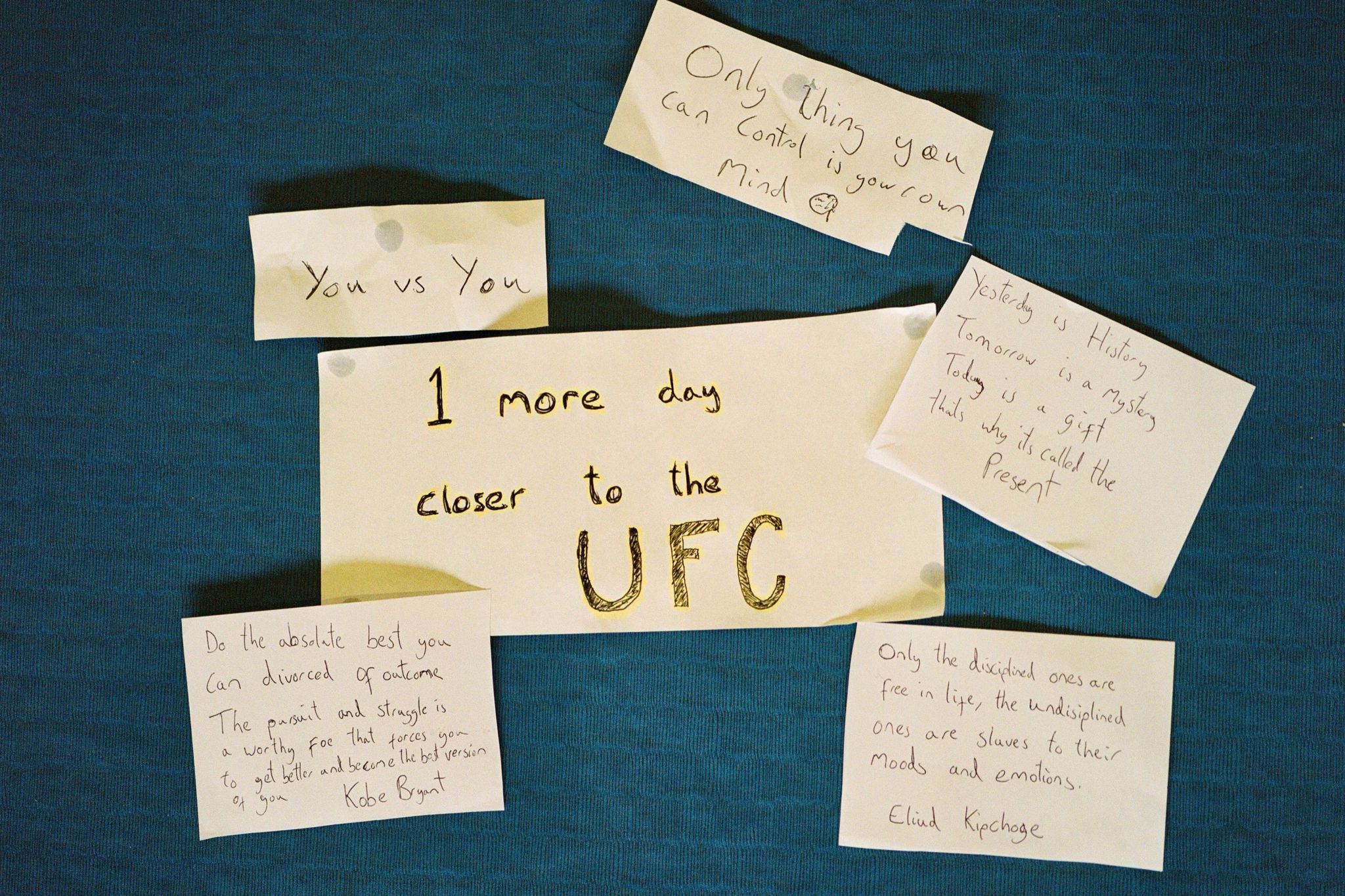

After back-to-back losses in November 2022 and July 2023, McCann dropped a weight division, worked hard on weaknesses in grappling and committed to “saying less and doing more”.

“I grew up doing karate-type boxing, just all striking really,” she says.

“I’d have a good go at grappling but it didn’t set my heart on fire. And then I lost twice by arm bar and it just slaughtered me.”

The work paid off. McCann made her as a strawweight in February, defeating Diana Belbita by arm bar.

“I also felt like it was my responsibility to give my heart and soul in interviews,” she adds of her previous approach to MMA.

“But people turned on me, so I don’t carry that any more. After my losses I had therapy to deal with trauma from my past and the professional stuff. I felt lighter after.

“So now it’s ‘say less, do more’. I will be better.”

Pimblett and McCann are two of the big draws at the new Co-op Live Arena in Manchester on 27 July. It will be somewhat of a homecoming; it’s the first time the pair have fought on a UFC card in the North West.

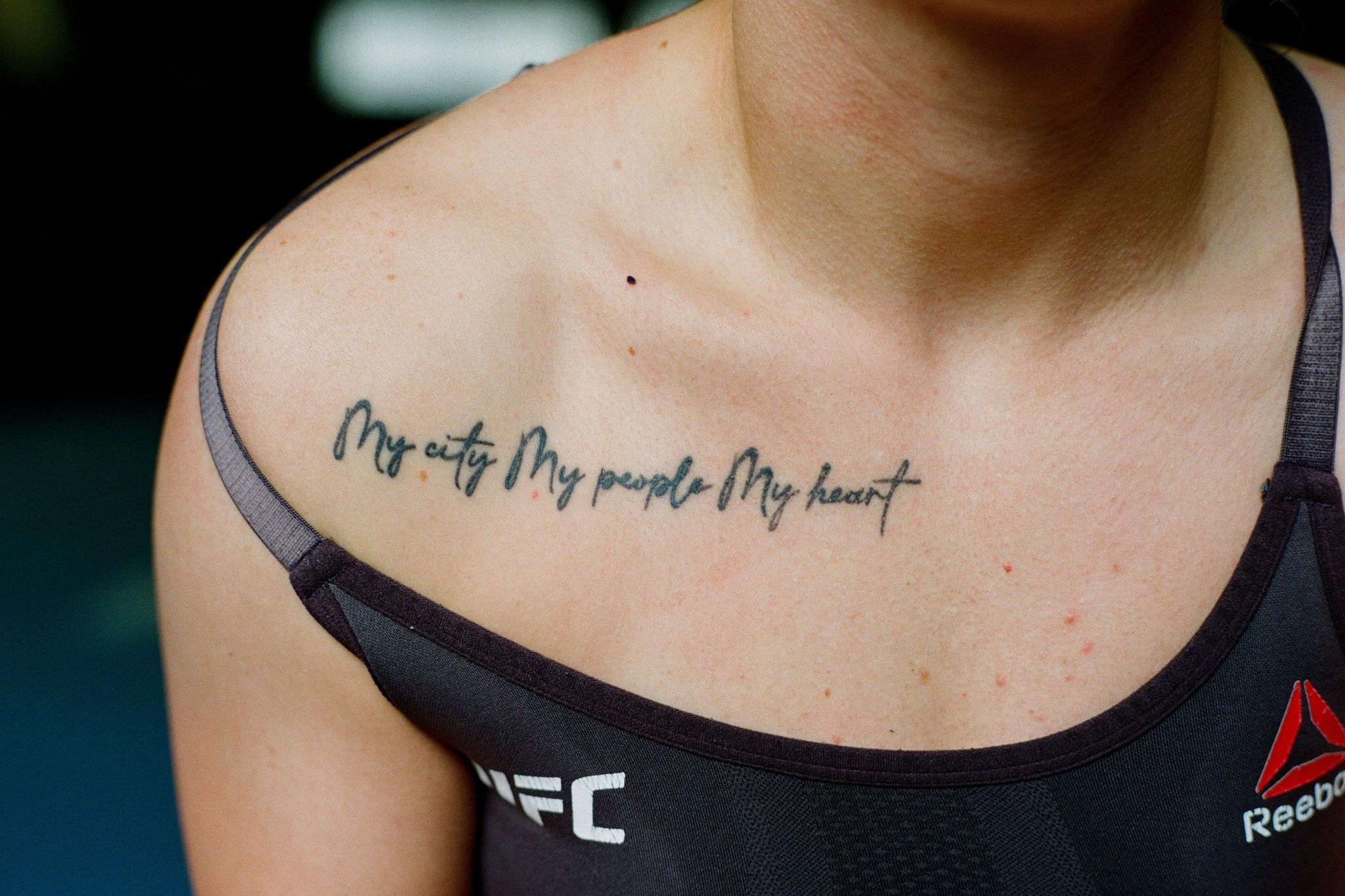

McCann’s fight style is more concise, reserved and harnessed, but her confidence is undimmed. She has promised to “destroy” opponent Bruna Brasil.

Cage Warriors fighter Adam Cullen also trains at Next Generation. Like McCann, the 26-year-old has experienced the unforgiving side of the MMA fanbase.

Cullen was on a seven-fight winning streak before suffering a knockout defeat in April 2023. He made a winning return in September but was on the wrong end of a split decision in March this year.

“It’s definitely a mental strain because one minute you’re the next big thing, then you lose one fight and people say you’re nothing,” he says.

“In the gym, you never feel alone or lost. Someone has always been through what you have. The actual fighting is what keeps you going back. You go from terrified to top of the world in seconds.”

Cullen was inspired to train at Next Generation by Pimblett’s early, pre-UFC success in MMA.

He turned up at the gym and soon found himself training alongside Pimblett and McCann.

It’s a defining characteristic of the gym. Despite its global UFC stars, there is no hierarchy. Everybody trains together regardless of external status.

Despite five wins from five fights in the UFC, Pimblett, like McCann and Cullen, has experienced the ups and downs of life in the octagon and outside of it.

In July 2022, he made headlines around the world after a sensational win over American Jordan Leavitt.

In an emotional post-fight interview, he appealed for men to talk about their mental health, revealing a friend had recently died by suicide.

Such is Pimblett’s charisma, warm-heartedness and authenticity, that Liverpool therapy centre James’ Place – a suicide prevention charity focused on men – reported a surge in enquiries following his speech.

“In this city, you hear it all the time about people killing themselves. When my friend took his own life I felt I had to say something. People praised me but I just felt I was doing my part as anyone in my position should be doing – it matters. It’s more important than fighting,” he says.

Fast forward six months though and it wasn’t praise he was hearing.

Pimblett was jeered when he was awarded a controversial decision victory over Jared Gordon in Las Vegas. Soon after, he attracted more criticism, following a dispute with MMA commentator Ariel Helwani.

“Everyone just proper changed on me,” he says. “I get on with it because it’s the sport I’m in. I’m not signed in to any of my social media because I’ll just start commenting back to people again.”

Pimblett will fight Bobby ‘King’ Green in July but had hoped to face the higher-ranked Renato Moicano.

He says training is focused on building up wrestling and sparring technique.

“When I grapple, I always feel confident. It’s my striking I have to improve.

“I feel like over the last fight camp or two, it’s come on leaps and bounds.”

The UFC main card will begin at 3am in Manchester, to tie in with American television.

It means the Next Generation Gym will be busy in the middle of the night for the few weeks before the fight, as Pimblett and McCann acclimatise.

It is also busy at home for Pimblett. In May, he became a father for the first time. He credits his wife Laura for caring for twins Betsy and Margot so he can sleep.

McCann is a board member and head coach at the English Mixed Martial Arts Association (EMMAA), helping to look after the sport’s next generation.

The EMMAA, among other things, supports pathways into competitive MMA for ages 12 and up.

At Next Generation, Rimmer’s own son Jack, 16, is set to start an apprenticeship at the gym, learning to coach and lead sessions.

His goal is to turn professional as a fighter and take over from his father one day.

“I’ve trained since I was five,” says Jack. “When my dad used to come home with belts from fights, I just knew I wanted to do it. Paddy was a big inspiration because of the way he built himself up to be a local hero.

“The gym brings everyone together no matter the age – whether you’re unfit or have disabilities, you can still train. And you can just make friends straight away and meet people from all different countries.”

Rimmer sees a city’s pride reflected back in the growth of his sport.

“The big jump will be in younger fighters now,” he says.

“These kids are coming in with a skillset and training from much earlier ages, since they were six.

“The work we’ve put into the legacy of MMA in Liverpool over the years won’t stop with me.”