An Olympic friendship that defied Hitler

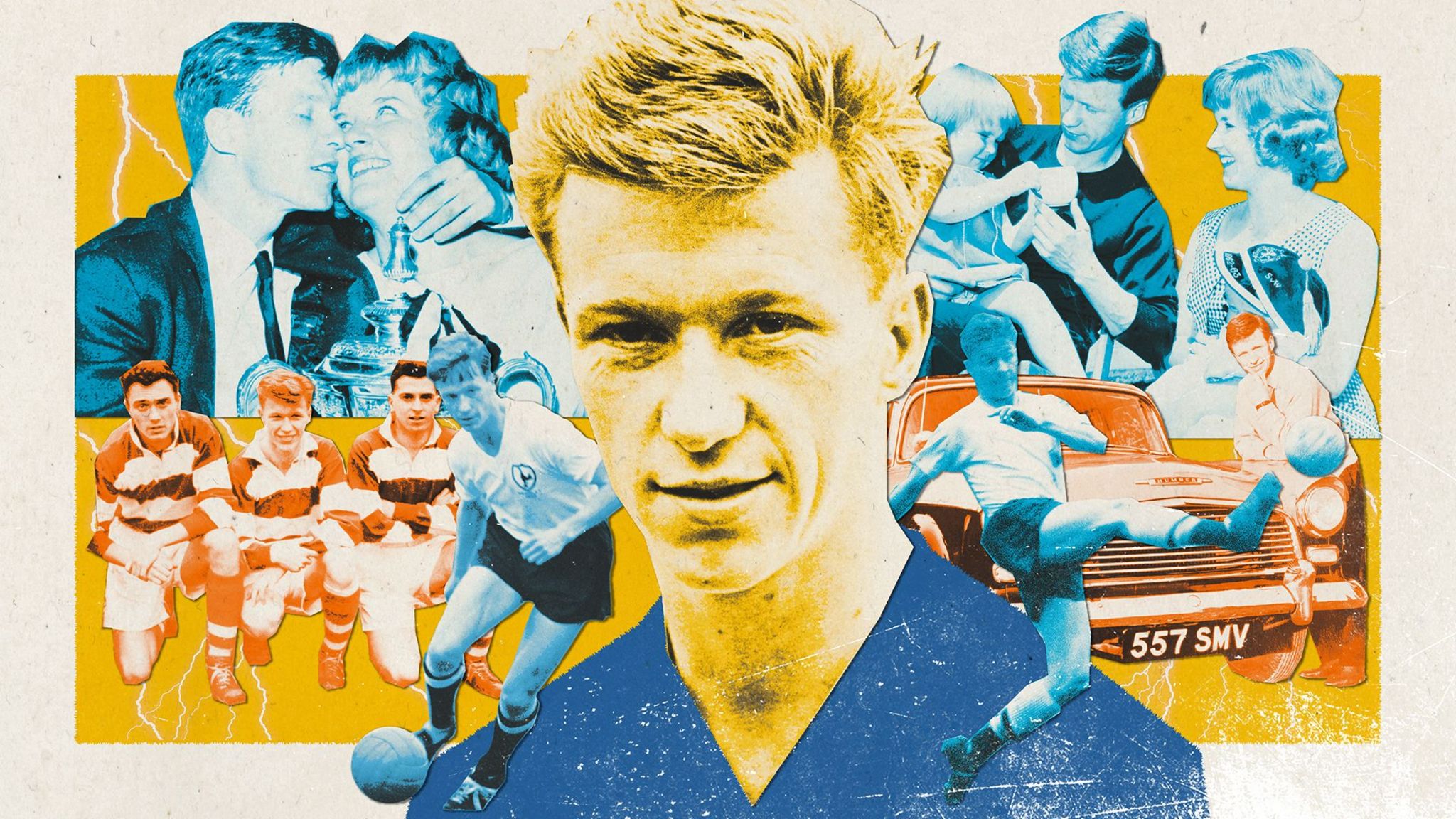

Jesse Owens and Luz Long’s embrace has become a defining image of Olympic sportsmanship, but it came with consequences.

It was an instinctive sporting gesture that has gone down in Olympic folklore, but, for German long-jump champion Luz Long, it would have dark consequences.

As Jesse Owens soared over the eight-metre mark to secure gold at the 1936 Games, Long – his biggest rival – leapt into the sandpit in Berlin to hug and congratulate him.

Later, in a striking contradiction to Nazi Germany’s twisted notion of Aryan supremacy and decades before the civil rights movement would spark radical change in the United States, the pair shared a lap of honour together, black and white athlete jogging arm in arm.

Not everyone was applauding. High in the stands, German leader Adolf Hitler watched on disapprovingly.

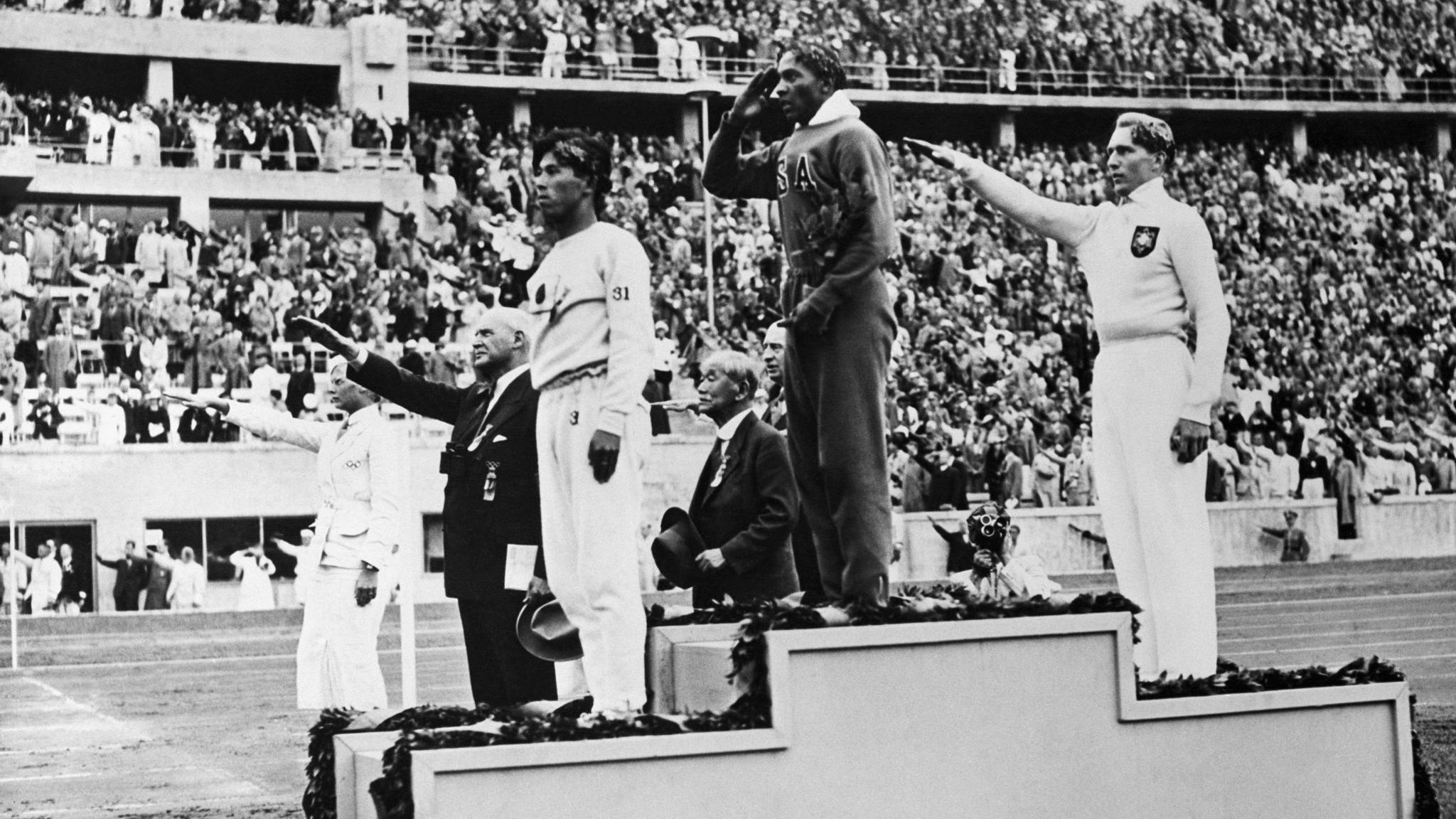

As they stood on the podium – Long giving the required Nazi salute and Owens saluting the Stars and Stripes flag of a nation not yet ready to accept him wholly as one of their own – both athletes were unaware of what lay in store.

Owens and Long, both born in 1913, were at the peak of their athletic powers when they locked horns in Berlin.

But that is where the similarities ended; their beginnings and journeys to the Games were polar opposites.

A 20th-century icon, Owens’ story has been widely told. He was the grandson of former slaves and the youngest of 10 children in a family of Alabama tenant farmers.

As a child, he picked cotton with the rest of his siblings, but his athletic ability became clear after the family moved to Cleveland and he was enrolled in school, aged nine.

He had gone by the nickname JC, short for James Cleveland, but after his teacher misheard him he was registered as Jesse and the name stuck.

Owens earned an athletic scholarship to attend Ohio State University where, under the tutelage of coach Larry Schnyder, he became one of the greatest sprinters the world has ever known.

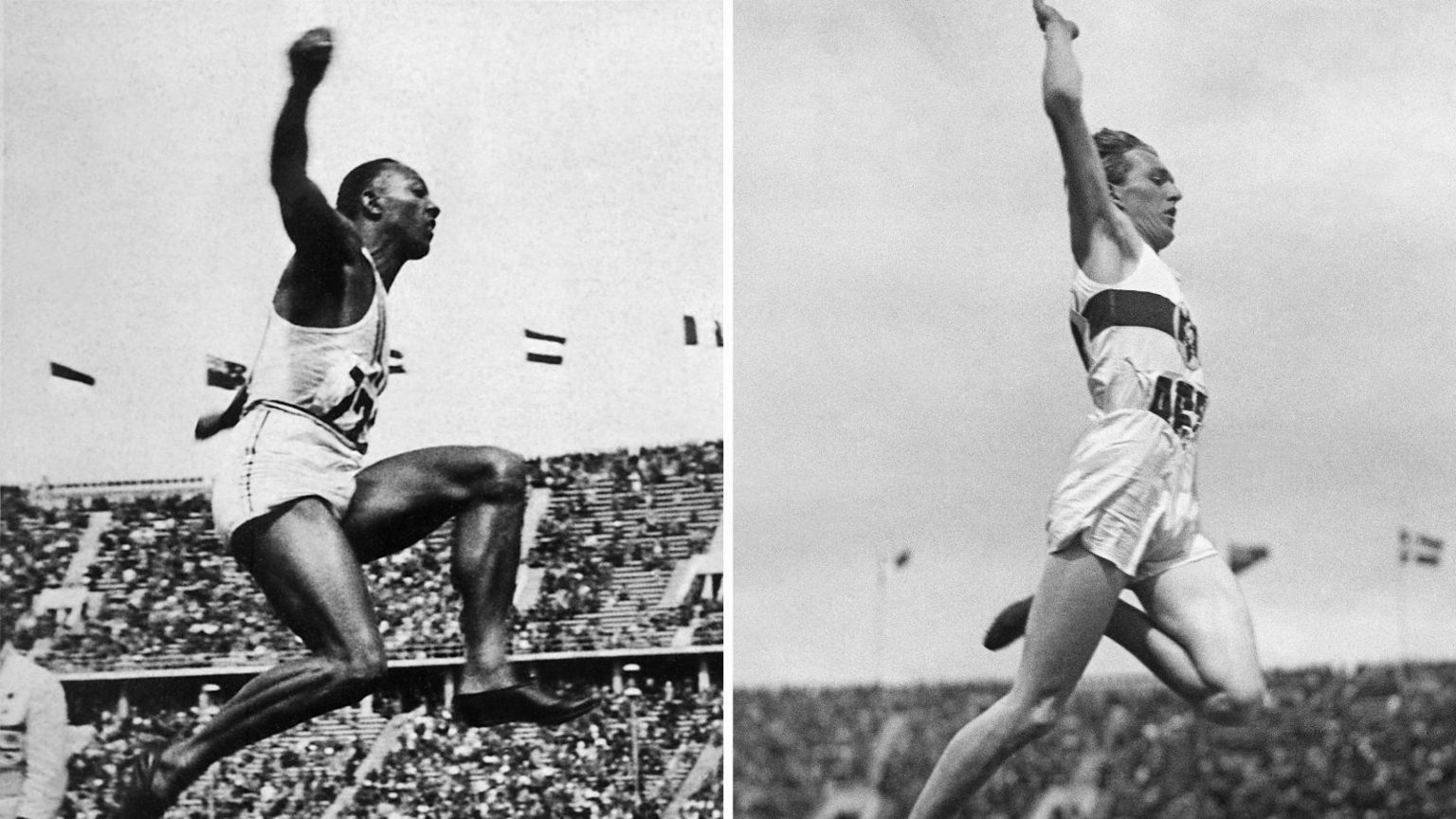

At a track and field meeting at the University of Michigan in 1935, Owens broke three world records and equalled another, all in the space of an hour, setting a new mark of 8.13m for the long jump that would stand for 25 years.

Unlike his rival, Long enjoyed a privileged upbringing, born into a middle-class family in Leipzig. His father, Karl, owned a pharmacy in the centre of the city, while his mother, Johanna, was a qualified English teacher. She came from a respected academic family, which included scientist Justus von Liebig, known as the founder of organic chemistry.

Carl Ludwig Hermann Long, who became known as Luz for short, grew up with his four siblings in the countryside outside the city. They would have family athletics championships in their sizeable back garden.

Long joined Leipzig Sport Club in 1928, where he came under the guidance of coach Georg Richter, who helped him develop a technique of sailing through the air using his strength as a high-jumper, unlike Owens, who harnessed his pace as a sprinter.

The partnership with Richter proved fruitful, as Long broke the German long jump record in 1933 to become national champion, aged just 20. Just a couple of months before the Berlin Olympics, Long set a new European long jump record of 7.82m en route to his third national title.

While both Owens and Long were building momentum on the track, they were also contending with the political landscape off it.

In the United States, there was growing pressure to boycott the Berlin Games in light of stories about the treatment of Jewish people in Germany under the new Nazi regime.

Owens initially supported calls for a boycott of the Games, reportedly telling the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People “if there are any minorities in Germany who are being discriminated against, the United States should withdraw”.

But he eventually agreed to attend following pleas from his coach and assurances from the United States Olympic Committee, who had sent a delegation to Germany to assess conditions and discuss the hosts’ policy on the participation of Jewish athletes.

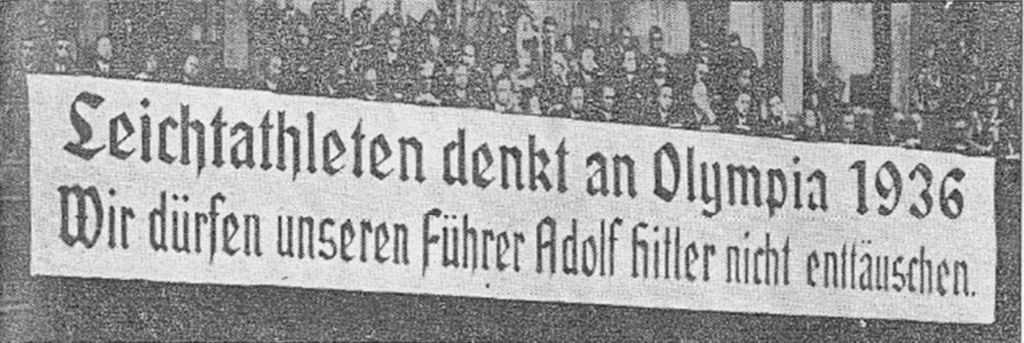

Back in Germany, the political pressure placed on athletes by the state was increasing.

“Athletes were representatives of the German Reich – both on and off the ash track – not private individuals,” says Julia Kellner-Long, Luz’s only grandchild.

Long’s rise to the national team came in 1933 – the same year Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany.

In the unlikelihood that he was unaware what was expected of him, a banner posted at the training ground made it clear: “Track and field athletes think of the 1936 Olympics. We must not disappoint our leader Adolf Hitler.”

Hitler was present at Berlin’s Olympic Stadium as Owens and Long contested one of the Games’ greatest long jump finals.

After a see-sawing battle, Long matched Owens’ leading distance of 7.87m with his penultimate attempt, to the delight of the home fans.

But Owens dug out his best when he needed it most, responding with 7.94m, to move clear of Long once again.

Long produced a foul on his final attempt, but his performance was good enough for silver and a first Olympic long jump medal for Germany.

Owens, with his title already assured, created further history with a final leap of 8.06m – setting an Olympic record that would stand for 24 years.

Long, putting aside his own disappointment, instinctively leapt into the sandpit to congratulate him.

Locked in that moment, alone in their embrace as an appreciative capacity crowd of more than 100,000 people watched on, Owens confided to his rival: “You forced me to give my best.”

Between them, Owens and Long had surpassed the previous Olympic record five times.

“It’s almost like a fairytale – to jump so long in this weather,” said Long in an interview with his hometown newspaper, Neue Leipziger Zeitung.

“I can’t help it. I run to him. I’m the first to congratulate him, to hug him.”

Long’s impulsive reaction caught the attention of the German authorities.

Soon after the Olympic Games, his mother, Johanna, made a note in her diary about a warning from Rudolf Hess, then deputy Fuhrer of the Nazi Party.

Long, she wrote, had “received an order from the highest authority” that he should never again embrace a black person.

He had been noted as “not racially conscious” by the Nazi regime.

The embrace clearly angered the Nazis, who often used powerful imagery to further its own ideology and feared how Owens and Long’s friendship might undermine its propaganda.

In that respect, they were right.

Almost 90 years later, Owens and Long’s friendship is one of the most enduring Olympic stories.

“The gesture of kindness and fairness touched the hearts of many people,” says Kellner-Long.

“Together, Luz and Jesse enjoyed a special friendship that day, demonstrating to the world that in sports and in life, friendship and respect are the most important things, regardless of background or skin colour.”

Stuart Rankin, Owens’ only grandson, is equally struck by its significance.

“I often say that of all my grandfather’s accomplishments at the 1936 Olympics, the unlikely friendship that he struck with Luz Long is the thing of which I am most proud and most impressed by,” he says.

“For them to have forged that friendship, under those conditions, in those circumstances, in that stadium, in the face of Hitler, was just phenomenal.”

It would be the only time Owens and Long would compete against each other.

Owens went on to add the 200m and 4x100m titles to his wins in the 100m and long jump and would take home four gold medals from the German capital.

But he angered authorities by refusing to compete in a meeting in Sweden immediately after the Games, instead returning home to take advantage of his new-found fame and a clutch of commercial opportunities.

The decision would result in Owens being banned from competing by the American Athletic Union – effectively ending his sporting career.

Owens was still given a hero’s welcome in a special homecoming ceremony in New York, but an incident at a party thrown in his honour at the Waldorf Astoria proved that despite his Olympic glory, nothing had changed.

On arriving at the hotel, Owens was directed away from the lobby by a doorman to a side entrance he was told was for tradesmen and black people.

It was a stark reminder of the deep-rooted division and racial prejudice at the heart of American society.

Long left Berlin as Olympic silver-medallist, national champion and European long-jump record holder.

He would go on to extend that mark to 7.90m the following year – a record that stood until 1956.

But he could not escape scrutiny or suspicion.

“Luz’s embrace in the sandpit had consequences,” says Kellner-Long.

“He was placed under closer monitoring by the authorities, compelling him to tread more carefully and maintain a lower profile.”

Long did not compete again after the outbreak of World War Two, instead focusing on his career as a lawyer.

Heinrich, his youngest brother, was killed in action. Devastated by the loss, Long attempted to plot a course through the war for his own family.

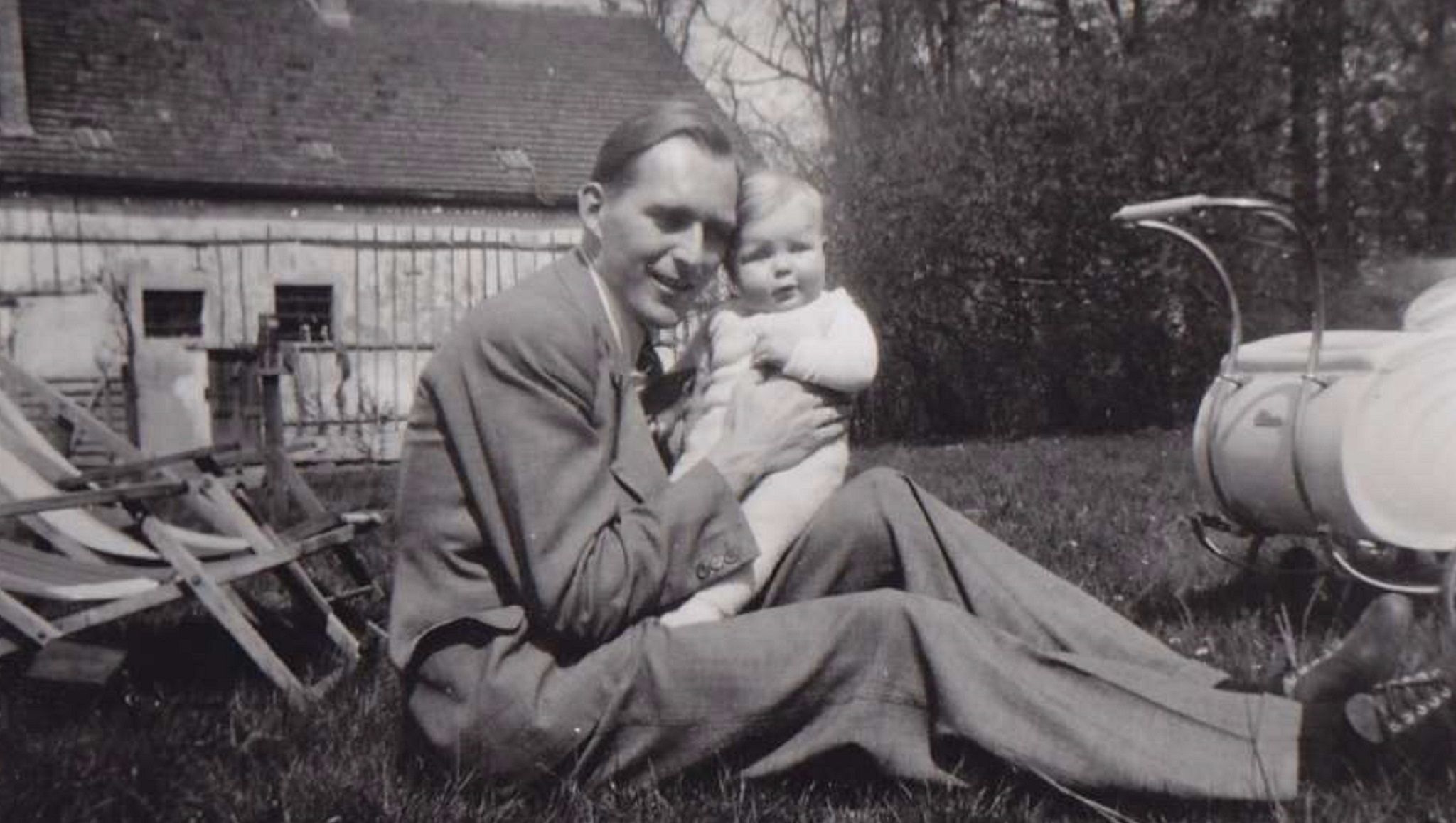

He married Gisela in 1941, and they had a son – Julia’s father – in November of that year, naming him Kai Heinrich, after his lost brother.

By then, Long had been drafted into the military, initially carrying out duties away from the frontline.

However, in 1943 Long was shipped out to Sicily with the 10th Battery Parachute Anti-Aircraft Regiment. A month later, he would send his final letter home to Gisela, who, by this time, was heavily pregnant with their second son, Wolfgang Matthias.

“In the letter, Luz described camping in tents on a beautiful flower meadow surrounded by mountains, a peaceful setting – that was his final communication with his family,” says Kellner-Long. “The next day, 30 May 1943, Wolfgang was born. Unfortunately, Luz never got to meet him.”

Allied forces landed in Sicily on 10 July 1943, as part of an operation to liberate Italy. Four days later, Long was hit in his leg by shrapnel, as German forces retreated, and bled to death.

Gisela received notification on 30 July that her husband was missing in action, presumed dead. It was only after another seven years that the details were confirmed and his grave, in the German section of honour at the American military cemetery in Gela, was found.

Owens chose not to enlist for military service during the war, and neither was he drafted.

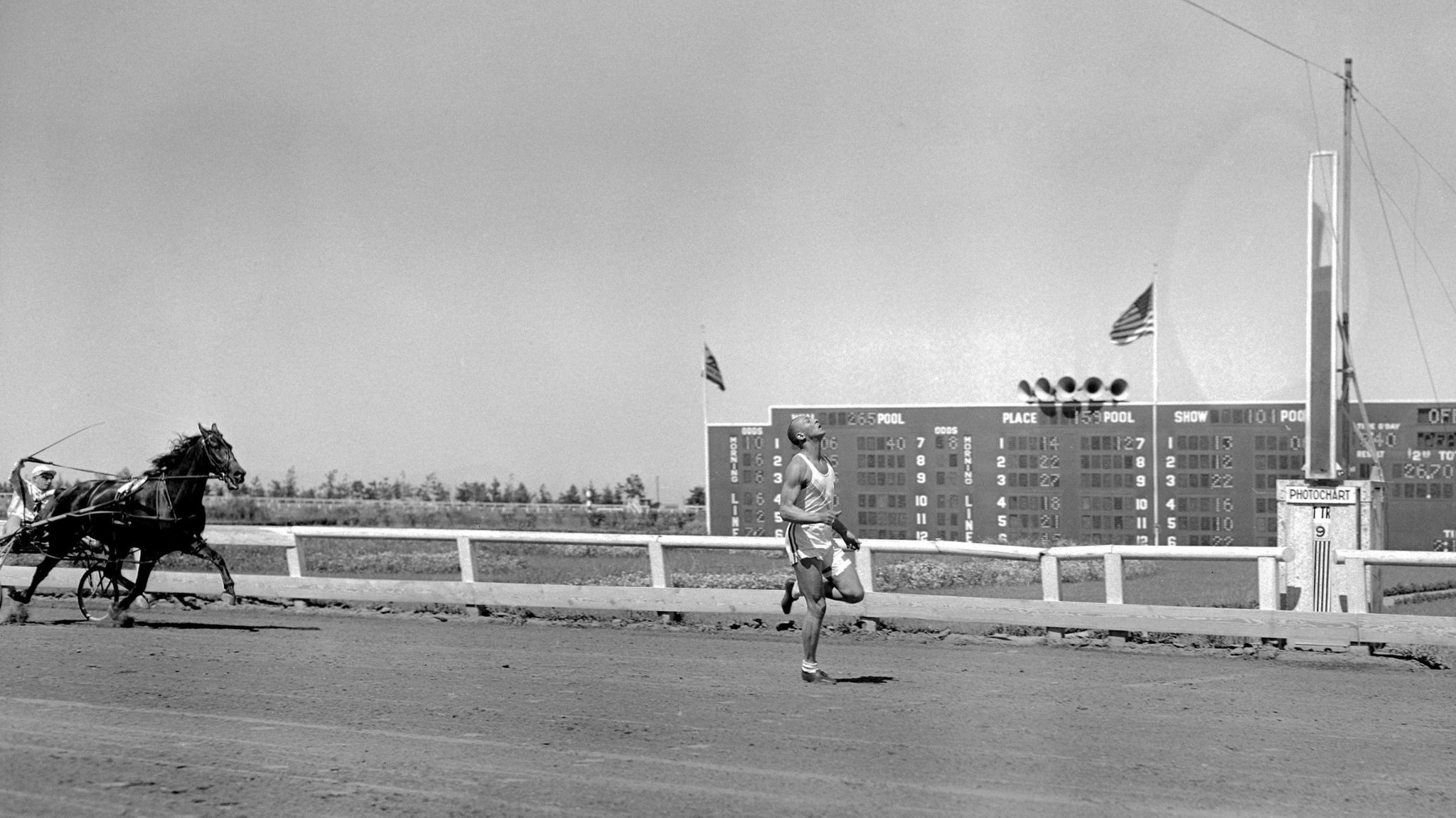

But, banned from official athletic competition and with commercial offers quickly drying up, he had to find unorthodox ways of supporting his family.

He would take on local sprinters, giving them a 10 or 20-yard head start, before reeling them in with ease to claim a cash prize.

Or, when his human rivals weren’t forthcoming, Owens would race motorbikes, cars, and horses.

“People say it was degrading for an Olympic champion to run against a horse,” Owens said, “but what was I supposed to do? I had four gold medals, but you can’t eat four gold medals.”

After flitting between menial jobs, things started to improve for Owens in the 1950s when he found employment as a motivational speaker. He started his own public relations business and became a sought-after figure, travelling around the globe as a sporting ambassador.

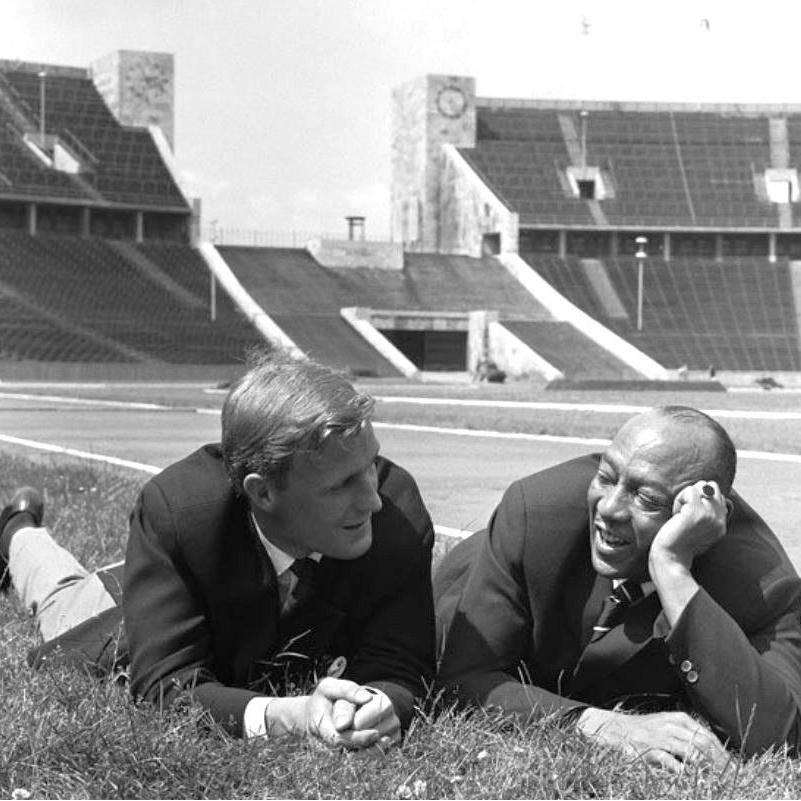

During a trip to Germany in 1951, with the Harlem Globetrotters basketball team, Owens reached out to Long’s family. He met Kai and took him to the Globetrotters game in Hamburg as his guest of honour.

In 1964, Kai took part in a documentary, Jesse Owens Returns To Berlin, during which the two recreated a picture of Owens and Long reclining trackside at Berlin’s Olympic Stadium.

“Kai admired Jesse so much – his charisma, his modesty, and his natural gift and success as an athlete,” says Kellner-Long.

Owens was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1976, before his death from lung cancer four years later, aged 66.

He was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1990. In 2016 then-president Barack Obama invited Owens’ relatives to the White House for a reception that Jesse and the other black members of the 1936 US Olympic team had been denied after Berlin.

His wife, Ruth, has continued his legacy, running the Jesse Owens Foundation before passing on the baton to their daughters – Gloria, Marlene and Beverly – and more recently their five grandchildren.

Over the years, the Long and Owens families have stayed in touch.

Julia Kellner-Long, along with Owens’ granddaughter Gina, lit the Olympic flame in a special ceremony at the Berlin Stadium in 2004. With Marlene, she then presented the long jump medals when the World Athletics Championships were held in Berlin in 2009.

Kellner-Long and Rankin would become close friends after a chance meeting in Munich in 2012, and have recently worked together on a documentary about their grandparents.

“The relationship between the families means a lot to me, and I am proud of our connection,” says Kellner-Long.

“Julia and I joke around often and think of both of our grandfathers looking down and smiling and being quite happy that the families are still connected despite the years,” adds Rankin.

While the reality of the friendship between Owens and Long is held dear by both families, their special bond has taken on a life of its own online.

One widely repeated myth involves a vivid letter supposedly written by Long to Owens from the “dry sand and wet blood” of north Africa. It calls on Owens to return to Germany to find his son if Long fails to make it home.

One of the lines reads: “Tell him, Jesse, what times were like when we not separated by war, tell him how things can be between men on this earth.”

Unbearably poignant, but almost certainly untrue.

Long never served in north Africa. Neither family have seen such a letter and both question the likelihood and logistics of it being written and delivered.

Kellner-Long understands the powerful message people continue to take from their story, however.

“It offers hope and inspiration to people worldwide,” she says. “In times when racism and exclusion are sadly still prevalent, this story is more relevant than ever.”

“I think that Luz’s example of sportsmanship is one that should be preserved and held high for all time,” says Rankin.

“My grandfather’s relationship with Luz is certainly one he never would have predicted but, because it happened, it provided a hopeful perspective in my grandfather, and certainly in me, that, despite the tide of an entire nation, it doesn’t mean every member of that nation is the same.

“Luz’s strength and character, it’s almost indescribable, but it demonstrates how in the most unlikeliest of places you can still find good.”