Fix palliative care before assisted dying is introduced, doctors urge

Leading end-of-life doctors warn system is struggling, and changing law could make situation worse.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFixing the struggling palliative care system must be an immediate priority for the government, now that MPs have backed changing the law to allow assisted dying, senior doctors say.

The Association for Palliative Medicine (APM) says there is a risk the funding needed to pay for doctors and the courts to oversee assisted dying could divert money away from care for the dying.

It is calling for a government-led commission to improve end-of-life care, warning shortages of funding and poor coordination is already denying dying people access.

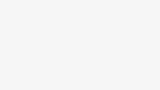

The intervention comes after MPs voted on Friday to back changing the law in England and Wales to allow assisted dying.

It is just the first parliamentary hurdle the bill needs to pass, with months more of debate and voting to come.

It is also possible the bill could fall and not become law at all.

Speaking to the BBC, Dr Sarah Cox, president of the APM, which is against assisted dying, said: “Health Secretary Wes Streeting said part of the reason he could not vote for assisted dying was because palliative care was not good enough. So I would say to him, now is the time to fix that.

“The UK is often held up as having the best palliative care in the world – but that is not the case any longer. We are not getting the funding we need.”

More on assisted dying:

Other

OtherThis week the Office for Health Economics said an increase in palliative care funding was crucial, with the system struggling to meet the needs of an ageing population.

At least three-quarters of people require palliative care at the end of their lives – that is around 450,000 people a year across the UK.

If you have an illness that cannot be cured, for example, palliative care aims to make you as comfortable as possible by managing your pain and other distressing symptoms.

But a recent report by end-of-life charity Marie Curie cited data showing around 100,000 go without, with half of families unhappy about the care their loved ones receive when they die. There are reports of people left in pain and with too little support.

Audits show four in 10 hospitals do not have specialist palliative care services available seven days a week.

Hospices, which provide care for around 300,000 people a year, are struggling for money. Around a third of their funding comes from the NHS, with the sector having to raise the rest themselves. A parliamentary report has described this funding system as “not fit for purpose”.

‘Neglected’

A number of MPs who backed the assisted dying bill claimed introducing it would help improve palliative care.

They pointed to a report by the Health and Care Committee which found in some countries it had been linked to an improvement.

But Dr Cox questioned this, saying it was a “very mixed picture”.

She added: “We know money is the NHS is finite – and our concern is that palliative care will lose out. The NHS will need doctors to assess patients, and judges to agree. That is all going to cost money, and palliative care is already struggling.”

More coordination between hospitals, community NHS teams, care homes and hospices is needed, and training for non-palliative care specialists is also an issue, she said.

Sam Royston, director of policy at Marie Curie, agreed action was needed on palliative care: “We have taken a neutral position on assisted dying, but we do not take a neutral position on the need for improvement on palliative care.

“The needs of people at the end of life are being neglected. There are no realistic plans currently in any UK nation to improve palliative care.”

He said just because MPs had backed assisted dying, did not automatically mean there would be improvements in palliative care too: “We had asked for a clause within the bill for a strategy around palliative care. If it does pass we will ask for this to be given greater attention.”

But Prof Sam Ahmedzai, a retired palliative care doctor and former NHS adviser on end-of-life care, said he had been to countries where both systems worked well in parallel with each other – and in some places where assisted dying had been introduced, palliative care had been improved.

He suggests more attention and training could be given to the people who provide the most palliative care – often GPs, district nurses and hospital doctors working in different departments.

The Department of Health and Social Care has been approached for comment.