‘Mums are dying and it’s so preventable’

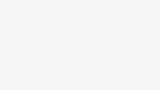

The family of a woman who ended her life while suffering postnatal depression say she was let down.

Family handout

Family handoutThe family of a woman who ended her own life after suffering postnatal depression for the second time say she was ‘let down’ by mental health services.

Lucy had struggled with her mental health after the birth of her first child, but was offered no extra support when the depression returned after her second, her family say.

They are calling on the government to end what they say is a postcode lottery of perinatal mental health care.

‘It’s like a living nightmare’

Lucy died on 23 September after going missing from a psychiatric unit in Scarborough where she had been staying as a voluntary inpatient.

After hours of searching with mountain rescue, her sister Faye was told that the “bubbly, caring and brilliant mum” had taken her own life.

“I just howled. It was unbelievable. It’s like a living nightmare for the whole family,” Faye said. “Her three-year-old is still asking when mummy is coming home and pointing to mummy’s side of the bed.”

But Lucy’s death was not out of the blue.

Family handout

Family handoutLucy started suffering from postnatal depression when her first baby turned three months old.

“She changed massively. A dark cloud came over her and took all of the life out of her,” Faye said.

“Any joy that she took from life was just gone. Her anxiety went through the roof. Her depression was horrendous. The insomnia and fatigue – it took over her life.”

Her parents moved Lucy and the baby into their home, she was prescribed antidepressants and at around the time her daughter turned one she began to recover.

“We had Lucy back and she was marvellous”, said her mum Ann.

Lucy told her family she did not recognise the person she was while she was suffering with the depression.

Family handout

Family handoutWhen Lucy fell pregnant with her second baby in 2023, her family were shocked to discover no extra support was provided.

“I assumed there would be more wraparound care, knowing she had depression with her first. But no extra support or care was offered”, Faye said.

After the birth of her son, the first three months were brilliant, her family say.

“She was an amazing mum. So creative. She did everything for her kids”, Faye added.

But again, the depression hit when her baby was three months old, and despite the best efforts of her family they said this time round it was even worse.

“We were floundering. We needed help as well. We gave her the medication and it was constantly being changed. It wasn’t working,” Ann said.

Lucy started talking seriously about taking her own life, and her husband contacted the crisis mental health team.

She received some counselling and home visits, and she was then referred to the perinatal team which provided weekly counselling sessions

But staff sickness meant face-to-face sessions were replaced with phone calls and her condition deteriorated.

In August she made an attempt on her life. She also started hearing voices, a sign of psychosis that can result from severe postnatal depression.

Family handout

Family handout“We were all absolutely terrified at this point. We were so lost and scared about how we could support her knowing what she had done”, Faye said.

Lucy was admitted to a psychiatric unit on a voluntary basis, which meant she could come and go freely.

She was offered the option of finding a bed in a mother and baby unit but turned it down, which Faye feels was a warning sign.

“She should have been sectioned and sent to a mother and baby unit automatically,” she said.

“If the mother doesn’t feel like they want to be with their baby, there should be alarm bells ringing.”

Eight days before she died, in her hospital journal, Lucy wrote “help me”.

Family handout

Family handoutOn the day Lucy died her mum visited her in hospital and took her out for lunch. It was the last time she saw her daughter alive – Lucy never returned to to the hospital, or home to her babies.

“No child should ever have to ask why their mummy isn’t coming home. No husband should be without their wife. And no parents should have to bury their daughter for something that is so treatable,” Faye said.

Family handout

Family handoutLucy’s death is part of a bigger picture.

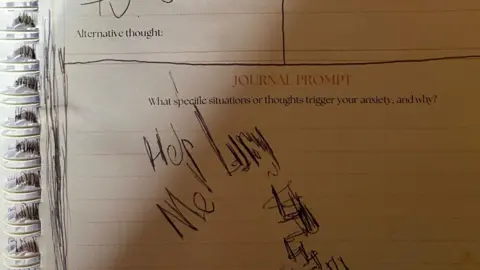

The postcode lottery of perinatal services is stark. Yet one in 10 women suffer from postnatal depression according to the NHS.

Research from the Maternal Mental Health Alliance (MMHA) reveals North Yorkshire, where Lucy lived, did not meet the care quality standards for perinatal care set by the Royal College of Psychiatrists 2023.

The orange sections of the map highlight the areas where staffing and services fall short.

Maternal Mental Health Alliance

Maternal Mental Health AllianceKaren Middleton, head of policy at MMHA, says mums are being failed by the lack of consistent maternal mental health care.

“Maternal mental health isn’t fully understood and has been historically under-invested,” she said.

“We need to raise awareness so commissioners and managers at the local level provide sustainable funding that is based on the levels of need in their area.”

Maternal suicide is the leading cause of direct death for mums when babies are between six weeks and one year old, according to the latest Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care (SLIMC) report.

This remains unchanged since 2009.

Care under review

A spokesperson for Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust said: “Our hearts go out to Lucy’s family and friends.

“We are looking closely at the care Lucy received from us and, in keeping with national guidance, we will establish if there is anything different we could have done to prevent Lucy’s death.

“We will support Lucy’s family through this process as their involvement is incredibly important.”

A spokesperson for NHS Humber and North Yorkshire Integrated Care Board (ICB) expressed their condolences to Lucy’s family and friends, and said it would “not be appropriate” to comment further while a review is under way.

The Department for Health and social care said it was “unacceptable” that anyone should feel let down by maternity support services.

“Specialist perinatal mental health services are established in all parts of England, but we know more is needed,” a spokesperson said.

“Too many people with mental health issues, including mothers who have recently given birth, are not getting the support or care they need.

“That’s why we’re reforming the Mental Health Act to fix the broken system and give more people greater say over their care.”

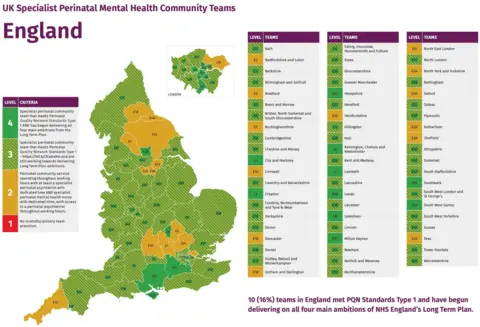

Family handout

Family handoutLucy’s family say she was a victim of the system. But they are determined to fight for change.

“Mummies are dying and it’s something so preventable. We’ve got a baby and three-year-old growing up without their mummy,” Faye said.

“We need to save the mummies.”

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this story, you can visit the BBC Action Line.

You can also email [email protected] to share your experiences.