Trump inherits waning US strength in Africa

By Jessica Donati

DAKAR (Reuters) -A decline in U.S. influence in Africa means U.S. President-elect Donald Trump’s administration will have to grapple with blind spots in its understanding of a fast-changing continent increasingly allied with China and Russia and threatened by spreading jihadist insurgencies.

Interviews with eight current and former officials along with a review of U.S. government watchdog reports show that a dearth of staff and resources under President Joe Biden at embassies in Africa undermined efforts to implement Washington’s goals.

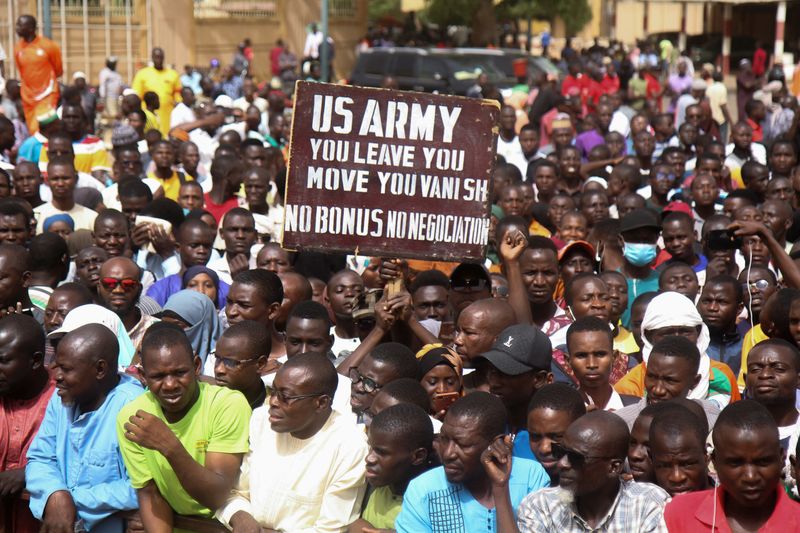

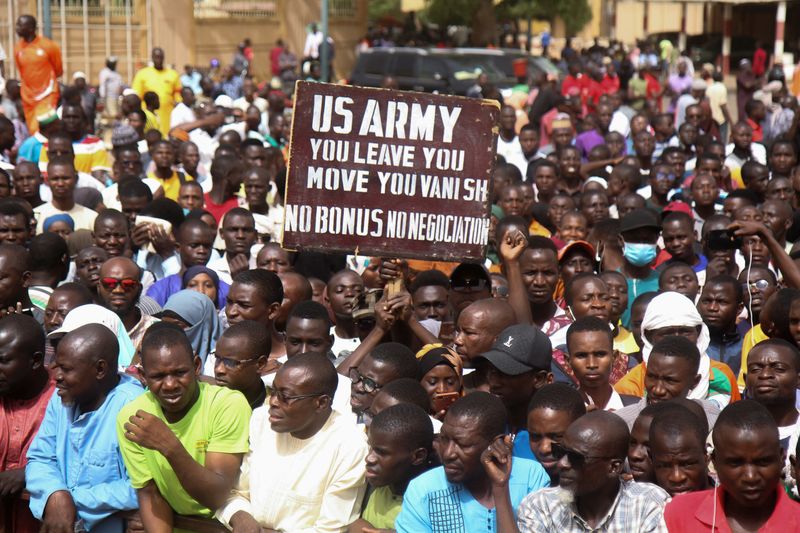

The U.S. racked up diplomatic setbacks over the past four years, including losing America’s major spy base in Niger and failing to negotiate a deal with any ally to reposition those assets. It is now caught without a foothold among the Sahel region’s Russia-backed military juntas just as the region becomes the world’s terrorism hotpot.

In soft power terms, a Gallup poll published this year showed that China surpassed the U.S. in popularity in Africa.

Cameron Hudson (NYSE:), a former CIA analyst who worked on Africa in a number of roles for both Democrat and Republican administrations, said the lack of resources had led to missteps.

These include being caught by surprise when war erupted in Sudan in April last year, he said, and bungling talks with Niger’s junta over its airbase.

“We have huge blind spots in our understanding of political dynamics, military dynamics in the countries where we are active,” Hudson, now at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, told Reuters. “This is a mega issue that U.S. diplomacy faces, and it’s particularly acute in Africa.”

In response to Reuters questions, the U.S. State Department said applicants for posts in Africa were dissuaded by insufficient schools, health care, and the remote nature of many postings, adding that monetary and non-monetary incentives were in place to encourage service in what it called difficult posts.

Other signs point to America’s decline in a region long considered to be a low priority for U.S. foreign policymakers.

Washington has made little progress towards advancing access to vast reserves of African minerals that it says are critical for national security. A flagship U.S.-backed railway project to export resources through Angola to the West is still years from completion.

Biden made sweeping political promises to Africa that he has yet to keep, including visiting during his presidency, which ends in January. He vowed to support the addition of two permanent seats for Africa at the U.N. Security Council and for the African Union to join the G20, but neither has happened.

Two former senior officials that served in Trump’s 2017-2021 administration said they expected him to pursue a more pragmatic approach than Biden, seeking tangible returns for U.S. spending in the region.

Competition with China will be a major focus, they both said, along with fresh support for U.S. businesses. The U.S. may also revisit its politics towards military leaders in the troubled Sahel, with less focus on democracy and human rights, they said.

“Africa policy needs a bit of realism,” said Tibor Nagy, a retired career ambassador and former Trump envoy to Africa. “I’m hoping that with a second Trump administration, where policy is more transactional, you can actually end up with more successes.”

The Trump campaign did not respond to emails requesting information about its plans for Africa. Brian Hook, a former Trump official overseeing the diplomatic transition at the State Department, did not respond to a request for comment.

“THE LIGHTS WERE OFF”

The troubled U.S. diplomatic footprint on the continent is visible in U.S. government data and official reports that are publicly available but have not appeared in the media.

Numerous reports by the State Department’s watchdog, the Office of the Inspector General, detail staffing problems at embassies that undermine U.S. goals including promoting political and economic stability.

One example is the situation in the Central African Republic, a gold-producing, increasingly authoritarian state that pays Russian mercenaries for protection while receiving millions in U.S. aid, according to a watchdog report in June.

The report described how embassy staffing shortages meant the U.S. ambassador in the country often had no note-taker at meetings. Sending documents could take hours due to a weak internet connection at the embassy.

Over $2 million worth of inventory was lost in 2023, linked partly to theft and fraud by local hires, the report said.

Even in places where the U.S. wants to compete with Beijing, a top national security priority, staffing problems are severe. At one point in 2023, a U.S. congressional official said, the political section was vacant in Guinea, home to the world’s largest bauxite reserves, with exports mostly destined for China.

“The entire department was empty, the lights were off,” the official told Reuters, on condition of anonymity to speak candidly.

In Togo, a coastal West African nation threatened by jihadists, the small U.S. embassy was unable to keep up with Washington’s demands after Togo was selected to pilot the bipartisan Global Fragility Act, a U.S. strategy to promote political stability around the world through 10-year plans, an inspector general report published in mid-2023 described.

The report blamed a lack of both staff and experience, with almost every U.S. official at the post serving in their job for the first time. The embassy declined additional funding for security assistance because it didn’t have the resources to spend it, the report said.

The State Department declined to comment on specific questions about embassy operations in the Central African Republic, Guinea and Togo.

CUTS, CUTS, CUTS

With major wars raging in Ukraine and the Middle East, Africa may well be low on Trump’s foreign policy priorities. He has yet to appoint an Africa team, in contrast to his defeated opponent U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris, who named a team for the region in the days before the Nov. 5 election.

During his last administration, many in the region were enraged when Trump reportedly referred to African nations as “shithole countries”. Close allies were hit with travel bans. Eritrea, Nigeria, Somalia, Sudan and Tanzania were among 13 countries on the list when he left office.

Peter Pham, a former top Trump envoy to Africa’s Great Lakes and Sahel region, said he did not expect a major drop in U.S. aid for Africa with the new government but that with Trump there was a higher chance assistance would be cut off if a country was perceived to be acting against U.S. interests.

“We have to be more intentional about that, and that means capable partners and accountability,” he said in an interview.

The first Trump administration proposed sweeping cuts to the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development and struggled to fill posts during its time in office. It also pulled funds from the United Nations and healthcare organizations that supported family planning.

The American Foreign Service Association, the union that represents U.S. diplomats, said that a shortage of mid-level staff, red tape and other institutional issues all contributed to the problems in Africa.

The State Department has been hiring above attrition for the first time in 15 years, Marcia Bernicat, the foreign service director general, said in an interview in September, citing initiatives to address mid-career shortages.

A quarter of the workforce is now made up of people hired since 2020, she said. Two studies are underway to review incentives to draw people to hard to fill jobs.

Despite these efforts, staffing levels in Africa changed little overall during Biden’s time in office after falling during the global pandemic.

Limited State Department data provided to Reuters shows the number of foreign service officers in Africa dipped to 2,057 in 2023 from 2,175 in December 2018.

“It’s frustrating for everyone involved,” Tom Yazdgerdi, the foreign service union president, told Reuters. “It’s not just a staffing issue – it’s a national security concern.”