4 potential scenarios—and 1 map—showing how the world will trade goods for the next decade, according to BCG

A return to global cooperation and peace or a worldwide escalation? Here’s what to expect from geopolitics and trade by 2032.

The world order is on shaky ground. A financial crisis, the global pandemic, regional conflicts, and high inflation have spurred humanity’s departure from the relative stability and openness of the 1990s and early 2000s. What’s more, some 70 countries and territories have held or will hold national elections this year—some of which could have profound effects on both domestic populations and global institutions.

In this environment, traditional strategic planning is rendered obsolete. Rather than being predictive or attempting to be exhaustive, we need to think in terms of scenarios—alternative visions of how the world might look—and assess the business impact of potential geopolitical events under these assumptions. For instance, many experts didn’t expect Russia’s military buildup on the Ukrainian border to become a full-blown invasion, and many multinationals didn’t hedge against the risk of war. After the invasion in February 2022, corporations were left scrambling to handle disrupted supply chains and inflationary pressures. This crisis may have been an unlikely scenario, but it was a plausible one.

The critical takeaway is that we need to consider scenarios for the 2030s—a time horizon beyond the typical two-to-three-year corporate planning cycle, but not so distant that the scenarios are too theoretical or academic to be useful.

How geopolitics could reshape the world by 2032

The least likely scenario today—because of stagnant WTO reforms, the UN’s inability to stop conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine, and the rise of protectionist industrial policies—is a return to the days of global cooperation and peace. Western-values-based global institutions and peace mechanisms would regain dominance, and as sanctions and conflicts recede, global trade would reach historic highs.

A more likely scenario envisions the proliferation of regional conflicts. Although total global trade would be stable, regionalization would shift its flows, and supply shocks would multiply. These disruptions would strain commodity markets, while sanctions complicate capital flows. Global talent flows would also be obstructed.

Sitting between the first two scenarios in terms of likelihood, based on the state of tensions in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait, Russia’s nuclear rhetoric, and the risk of full-scale conflict in the Middle East, is a possibility of global escalation as major powers become directly involved. Global trade would plunge, and supply chains would go local. Technological innovation would focus on warfare and cybersecurity, and talent mobility would grind to a halt.

Currently, the scenario with the most momentum is defined by multipolar rivalry—consider the revitalization of NATO in the last two years, the recent expansion of BRICS, and the “no-limits” friendship between China and Russia. In this scenario, competing poles coexist. With limited trust among these blocs, they would form their own norms, institutions, tech stacks, and trade platforms. In decoupled global financial markets, access to capital would be limited. Innovation and climate policy would also be polarized. Though total global trade would be stable, trade lanes would shift, and preferred partners would trade within poles, not between them.

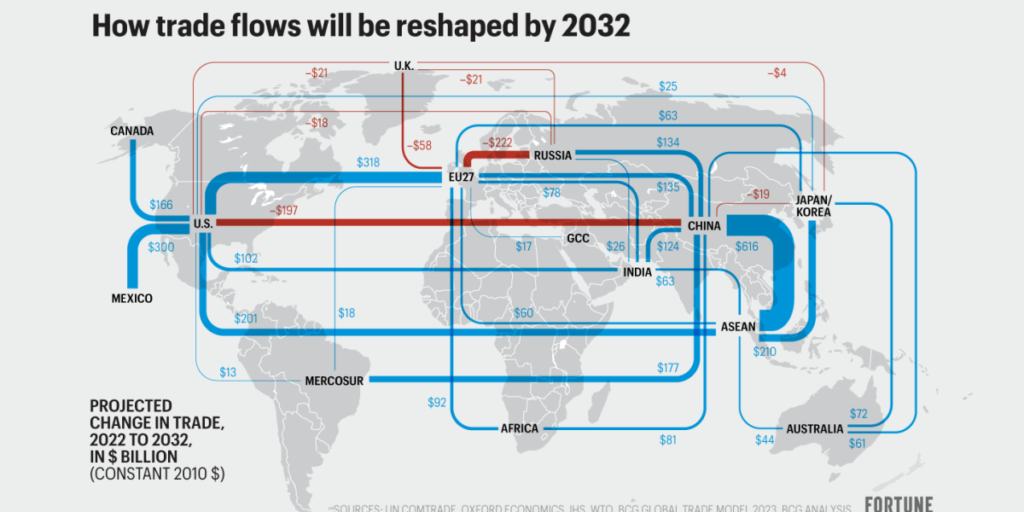

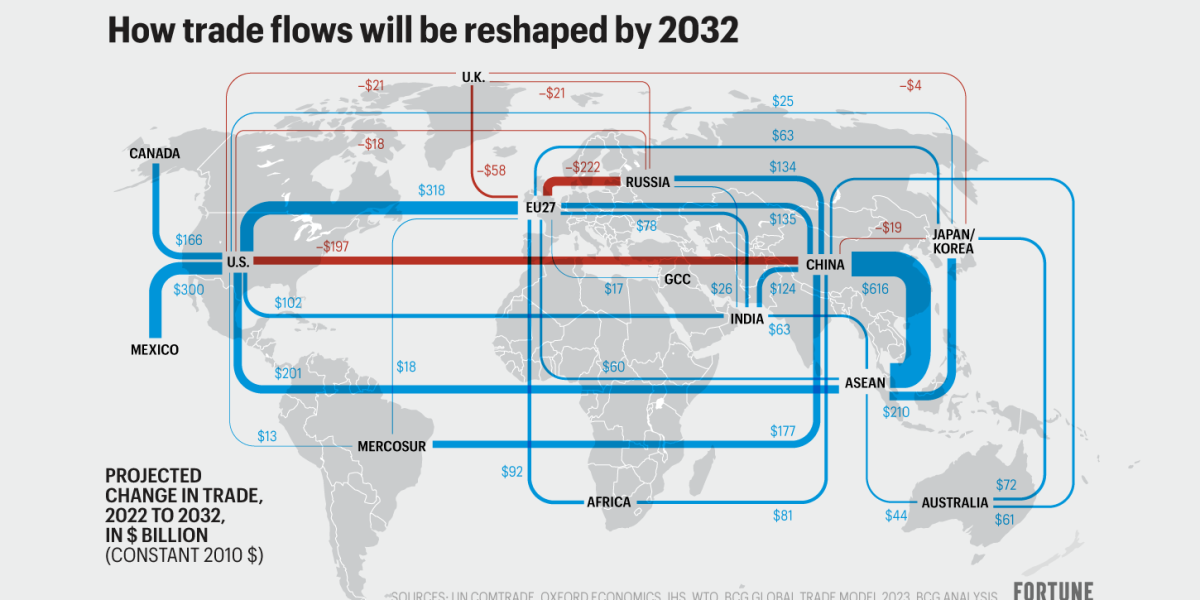

The shifting global trade map

Our analysis of more than 500 million data points, as well as macroeconomic and geopolitical drivers such as GDP growth, the evolution of free trade agreements, potential tariff policies, and export restrictions, has confirmed that distinct poles will be the drivers of global trade activity—a prime illustration of the multipolar scenario.

A powerful pole is developing in North America. U.S. trade with Canada and Mexico is forecast to increase by $466 billion over the next decade. Recent U.S. policies, such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), CHIPS Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are reinforcing the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and resulting in more reshoring and nearshoring. The IRA, for instance, includes “Buy North American” incentives.

While trade flows within North America grow, we forecast that trade between the U.S. and China will drop by $197 billion by 2032, amid continued tensions and barriers. Over the same period, trade between China and Southeast Asia is expected to grow by an impressive $616 billion. Southeast Asian nations will also see a surge in trade with Japan and South Korea. In total, additional trade from and to Southeast Asia will reach more than $1.4 trillion—largely driven by a diversification of supply chains away from China, as well as a favorable trade environment in many ASEAN countries.

Another pole is emerging among the BRICS. When Russia’s trade with the U.S. and the EU was disrupted by its war in Ukraine, it looked to its fellow BRICS nations to bridge the gap. So while Russia’s trade with the EU will fall by $222 billion by 2032 compared with 2022, its trade with China and India will grow by $134 billion and $26 billion, respectively. This trade diversion trend should be considered alongside the evolution of BRICS+. The 10 BRICS+ nations currently account for half the world’s population, two-fifths of global trade, and around 40% of both crude oil production and exports—and 12 more nations have applied for membership.

Of course, global trade is just one lens. Scenarios can reveal how various conditions will affect such macroeconomic indicators as GDP growth, inflation, oil prices, the trajectory of global warming, and international migration, to name a few.

In this fast-changing world, geopolitics must become a strategic priority for all companies—their future depends on it. The time to start is now.

More must-read commentary published by Fortune:

The opinions expressed in Fortune.com commentary pieces are solely the views of their authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of Fortune.