The awkward questions behind Hungary’s football revival

Hungary have ridden back into contention for international honours on the back of billions of euros and one man’s passion for football.

In the village of Felcsut, there stands a stadium.

Felcsut, 28 miles outside of Budapest, is home to fewer than 2,000 people. Yet the stadium seats nearly 4,000.

And in some style. Its roof – covered in slate tiles and copper turrets – is supported by soaring wooden columns, all set off with artful architectural lighting.

It is estimated to have cost more than £10m.

It is called the Pancho Arena – part monument to Hungary’s past, part statement of its future.

Seventy years ago – 150 miles south of Stuttgart, where the two teams’ met at Euro 2024 on Wednesday – Hungary faced West Germany in the World Cup final.

Having beaten the Germans 8-3 in the group stage, Hungary were hot favourites to win the final in Bern, Switzerland. But, after taking a two-goal lead inside eight minutes, they were sensationally defeated 3-2, losing their first game in five years and breaking a 31-match unbeaten run.

They never scaled such heights again.

Hungary’s stellar group of players – known as the ‘Mighty Magyars’ or ‘Golden Team’ – broke up two years later, many of its members choosing not to return home after the Hungarian Uprising of October 1956 had been violently crushed by the Soviet Union.

The finest of them all – Hungary’s captain Ferenc Puskas – wound up at Real Madrid, where he was given the nickname ‘Pancho’.

The stadium in Felcsut bears Puskas’ nickname thanks to the village’s most famous resident – Hungary’s football-crazy Prime Minister Viktor Orban.

First elected in 1998 at the age of 35, and now the longest-serving leader in the European Union, Orban has transformed Hungary, rewriting the country’s constitution and election laws. What he has changed it into is open to debate. Orban has described his approach as “illiberal democracy” and “Christian democracy”.

In 2022, the European Parliament opted for a “hybrid regime of electoral autocracy”, accusing Orban and his government of “deliberate and systematic efforts to undermine European values”.

On the new stadium in his hometown, Orban is certain however.

“It’s art,” he said in February 2017.

“It would be easier to build up something more simple, you know, but this is evidence that football is part of art.”

Orban wasn’t born when Hungary played in the 1954 World Cup final, yet his childhood passion for the game was fuelled by the near-mythical tales of the ‘Golden Team’.

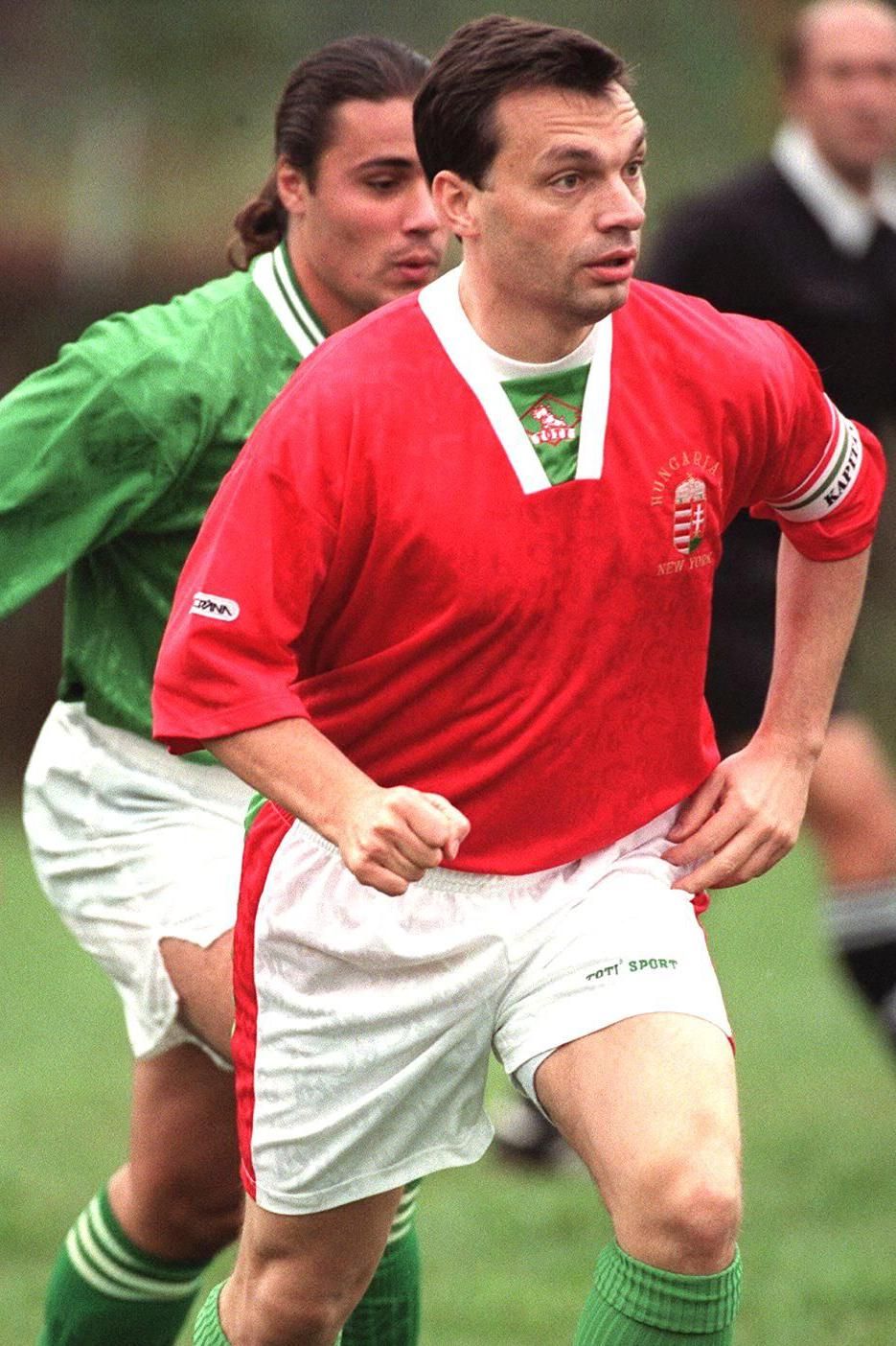

Orban was a good footballer as well. He played for the youth team of top-flight team Fehervar (known as Videoton at the time), before law school and a political career – supercharged by the fall of communism in Eastern Europe in 1989 – focused his career aspirations elsewhere.

His coach once described him as “quick on the ball” – a talent that has translated to his political career – and during his first term as prime minister, he would still turn out for his home village’s team.

“You can’t imagine the abuse I got,” said Orban. “But then I scored…”

When Orban and his Fidesz party suffered election defeats in 2002 and 2006, he retreated to Felcsut and football.

He would phone up old friends to arrange impromptu kickabouts. In 2007, Orban founded a new club there – the Puskas Academy. He reportedly invited then Arsenal manager Arsene Wenger to the inauguration ceremony. Wenger, it is said, politely declined.

In 2014, the Pancho Arena opened as the Puskas Academy climbed towards Hungary’s top flight.

But, back in power since 2010, football is no longer just a hobby for Orban.

It is increasingly a tool for influencing his allies, the Hungarian populace and even those beyond, with businessmen close to him acquiring clubs in neighbouring countries.

“Football is Orban’s pet project,” said Marton Tompos, an MP for Momentum, the Hungarian opposition party.

“If you are an aspiring oligarch or someone who wants to be close to the system, then you have to give back in a way that then you support your local football team.”

Orban’s government introduced the Tao programme – a scheme that enabled corporations to write off donations to clubs in certain sports as a tax deduction.

The effects since its introduction in 2011 have been marked.

“A complete infrastructural overhaul was carried out in the last decade,” said Henrik Hegedus, who is head of data at Hungary’s most popular football club Ferencvaros, having previously worked at the Hungarian Football Association for seven years.

“More than 20 stadiums have been built, well over 1,000 pitches built or renovated. Hungary play with sold-out stadiums at home, 60,000 attend even friendly games.”

But questions have been asked about whether the benefits – with an estimated 923bn Hungarian forints (£2bn) of potential government income directed to sports clubs instead – have been shared equally.

The Puskas Academy, founded by Orban in his hometown, has benefited most, with one November 2021 estimate that it had received 36.3bn Hungarian forints (£78m) over the previous decade.

Mezokovesd Zsory was the second-best funded club of that year, receiving 552m Hungarian forints (£1.2m).

A small club in a town of 17,000 people, Mezokovesd have Andras Tallai, the former tax office chief and current secretary of state for parliamentary affairs and taxation, as their president.

The vast majority of Hungarian top-flight clubs are similarly owned or run by Orban’s allies or officials from his party.

Orban’s government has attempted to keep secret the exact figures and the identity of those making use of Tao’s sporting tax break.

But the prime minister has been forthright in his defence of the scheme.

“It is a success story,” he told Nemzeti Sport in December 2020.

“Not only has it brought more resources to sports and made it easier for associations to operate, but, more importantly, a relationship has been established between business organisations, companies and sports organisations.

“Until the introduction of the Tao, the world of entrepreneurs and sports did not maintain any relationship with each other.

“I don’t think it’s a normal attitude to regret spending money on sports fields or for children to play sports.”

According to the estimates of the Hungarian FA and the Foreign Ministry, there are 50,000 Hungary fans at Euro 2024. Among that number are the black-shirted Carpathian Brigade, the nation’s infamous ultra-group, made up of fans from different Hungarian clubs.

Since 2009, they have been at every Hungary home and away game, leading chants and marches, waving torches and setting off flares.

Their repeated discriminatory behaviour has incurred punishment from Uefa, although the Hungarian football association exploited a loophole around the admission of children, and the need for accompanying adults, to play a “behind-closed-doors” fixture against England in front of 30,000 fans in May 2022.

Orban has stood up for the Carpathian Brigade.

After the Republic of Ireland’s players were jeered for taking a knee in support of racial justice before a friendly in Ujpest in June 2021, Orban accused the visitors of “provoking” local fans, saying he agreed with the sentiment in the stands, if not how it was expressed.

“Hungarians only kneel before God, homeland and when they propose to their love,” said Orban.

The Carpathian Brigade are a disparate bunch; one section saves abused animals in its spare time.

However the inner core has a habit of turning up at opportune moments for Orban’s government, such as in the corridor of the National Referendum Office to block a Socialist Party MP from registering a referendum petition, and manhandling environmental activists protesting against the cutting down of trees in Budapest’s City Park.

The team they support have been on the rise.

Hungary were unbeaten in their 14 matches prior to the tournament, a run unprecedented since the days of Puskas. In national team captain Dominik Szoboszlai, they have a genuine Premier League star for the first time.

Their two defeats so far in Euro 2024 have been deflating, with Wednesday’s 2-0 defeat by old rivals Germany particularly painful.

The fixture has become a regular trope in the Orban-friendly media, with Germany depicted as symbolic of the decadent west.

Before Hungary and Germany’s meeting in the Euro 2020 group stages, Uefa prevented Munich’s mayor from lighting up the outside of the Allianz Arena in rainbow colours.

The proposal had been motivated partly by protest at a ban of the depiction or promotion of homosexuality to under-18s in Hungary.

Critics say that the Child Protection Law brought in by the Orban government conflates homosexuality and paedophilia.

In the absence of an official show of solidarity with the LGBTQ+ community, a Germany fan ran on to the pitch with a rainbow flag while the Hungarian anthem was played before the game.

The issue of gay rights was already a divisive one in Hungarian football.

Hungary goalkeeper Peter Gulacsi, a former Liverpool player, now at RB Leipzig, had posted on Facebook a few months earlier in support of “rainbow families”.

“The more time I spend abroad or among people from different cultures, the more I realise the world is more colourful due to the fact that we are not all the same, and that love, acceptance, and tolerance are the most important things,” he wrote.

Hertha Berlin’s Hungarian goalkeeping coach Zsolt Petry responded in an interview with Fidesz-friendly daily Magyar Nemzet, saying that although Gulacsi was entitled to his own opinion: “Europe is a Christian continent and I can hardly bear to watch the moral degradation sweeping across our continent.”

Hertha Berlin sacked Petry over his comments.

Even Szoboszlai – Hungary’s brightest light who has emerged from the same region of Hungary as Orban and has steadily managed to avoid controversy – has been drawn into cultural debate, receiving criticism for taking the knee while playing for Liverpool, having not done so in two Nations League games against England in the summer of 2022.

On the pitch, there is an unanswered question at the heart of Orban’s project: how much of the success of the national football team is down to the billions he has lavished on the sport?

While young players at small local clubs have enjoyed new kit, facilities and equipment, key members of the squad such as RB Leipzig’s Willy Orban and Barnsley’s Callum Styles grew up outside the country, qualifying for Hungary through parentage.

Paris-born Loic Nego didn’t have any connection to Hungary but gained citizenship after eight years playing there. Marton Dardai was born and raised in Germany and represented them at age-grade level before opting to play for Hungary.

Perhaps the most important import of all is Italian manager Marco Rossi, who has overseen Hungary’s steady development over the past six years.

For Orban, though, the symbols are perhaps more powerful than the individuals.

His football project has added a new historical layer to Hungary, where communist-era tower blocks, grand Austro-Hungarian buildings, and Ottoman baths betray a tumultuous past.

If the Pancho Arena is closest to his heart, the national stadium in Budapest is the biggest example of his and the government’s adoption of football.

Similar to Bayern Munich’s Allianz Arena in size and design, but built at three times the cost, it stands on the former site of the rickety, historic Nepstadion.

In an otherwise unremarkable 1-0 friendly win over Estonia there in March 2023, the most dramatic moment came as a single, repeated phrase boomed out of the public address system.

The stadium’s tannoy announcer chanted: “Down with Trianon, down with Trianon.”

The Trianon Treaty was the agreement that reduced Hungary’s size by two-thirds in 1920.

Millions of ethnic Hungarians still reside within pre-Trianon Greater Hungary – the old imperial territory that existed before Austria-Hungary’s defeat in World War One.

The stadium announcer was only following Orban’s lead. Four months before, the prime minister had posted video of himself congratulating winger Balazs Dzsudzsak on his retirement from international duty.

Around Orban’s neck was a scarf featuring an image of Greater Hungary.

Ukraine, invaded by Russia earlier that year, summoned Hungary’s ambassador to explain another apparent claim on its territory. Romania, which took over Transylvania in 1920 and is still home to 1.2 million ethnic Hungarians, voiced “firm disapproval” of Orban’s gesture.

For many Hungary fans though, it tapped into a deep sense of historical injustice.

As the public address system denounced the loss of former Hungarian territories, as war raged over the border in Ukraine where some 200,000 ethnic Hungarians reside, no discernible surprise was visible among the crowd, so blurred have the lines between football and incendiary nationalist politics become in Orban’s Hungary.

“The essence of the football is like the essence of politics,” said Orban, who has been the most prominent pro-Russian voice in the European Union.

“Because the question is not where the ball is now – everybody can see where the ball is now – but the question is where the ball will be…

“If you understand earlier than others what will happen, you can react first and you can win.”