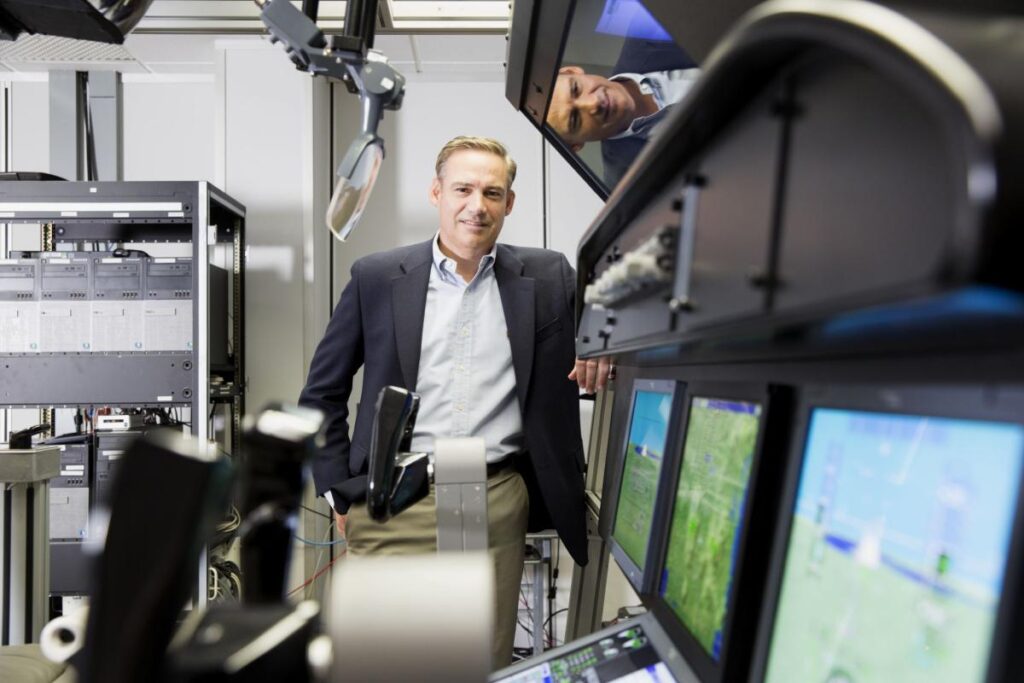

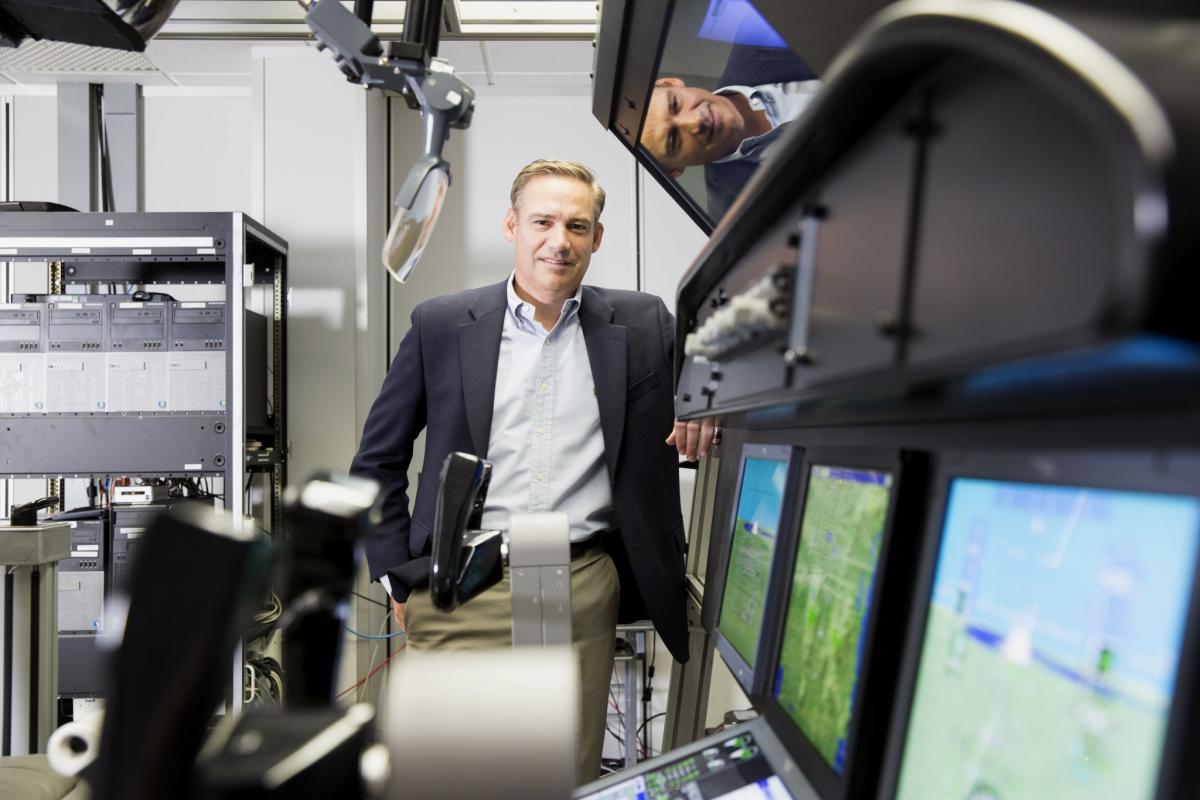

New Boeing CEO Kelly Ortberg abruptly left the game 4 years ago—but some think this ‘engineering visionary’ could chart a new path

On July 31, shortly after posting another round of disappointing earnings for Q2, the Boeing Co. announced that its new CEO will be Kelly Ortberg, former chief of aerospace giant Rockwell Collins. Ortberg’s choice was something of a surprise. His name hadn’t been mentioned as a candidate until the previous day, when aviation news site Air Current reported that the board had placed him at or near the top of its short list. Even in speculative chatter on the search, Ortberg hadn’t been mentioned, in part because he’d left his previous top job heading aerospace at RTX five years ago, and hadn’t taken an operating position since. Ortberg’s also 64, deemed at the high end of the age range for a leader who ideally would shepherd the planemaker through the several-year development cycle for the all-new, clean-sheet plane that will be crucial in charting the future for Boeing. (Boeing waived its mandatory retirement age of 65 for Ortberg.)

After a search where the Boeing board had relatively few good options, and such preferred picks as Larry Culp of GE Aerospace and Dave Gitlin of Carrier Global weren’t available, Boeing had narrowed the field to three outsiders, according to sources who spoke to Fortune. High on the roster was Pat Shanahan, a former top Boeing executive who now runs Spirit Aerosystems, the Boeing fuselage supplier that it recently agreed to acquire. But my sources indicate that current CEO David Calhoun didn’t want Shanahan, who’s known as a highly aggressive, no-nonsense manufacturing specialist who commands respect on the factory floor. Though Stephanie Pope, the commercial airplanes chief and former CFO, was widely cited as one of the top three, my sources all stated that the Boeing board was strictly set on an outsider who could reform its wounded culture to focus on quality and reliability in manufacturing, and at the same time provide a long-term vision that encompasses plans for a long-overdue next-gen aircraft that would bolster Boeing’s fading position versus Airbus in the narrow-body market for the decades ahead. (Information on Ortberg’s pay package hasn’t yet been disclosed.)

Ortberg will become CEO on Aug. 8, replacing Calhoun, who had pledged in March to retire by year end, following the notorious door-plug blowout over Portland, Ore. on Jan. 5. “He brings a total outside perspective, which is what Boeing needs, whereas perhaps Shanahan was seen as something of an insider because of his long tenure there,” says Rob Spingarn, an analyst with Melius Research. “Kelly’s both an engineer and an engineering visionary.” The job, notes Spingarn, will require just the kind of managerial dexterity that have long been Ortberg’s hallmark: “He’s capable of fixing the management floor with his left hand and choosing the right new plane with his right hand, and he’ll choose the staffing to help achieve both those short and long-horizon goals.” In a positive development, Dominick Gates of the Seattle Times cites sources saying that Ortberg will run Boeing from Seattle, a sign that the board may return its headquarters from Virginia to the place it was born, and the heart of its commercial airplane production.

The pressure will be on right away: In his first weeks, Ortberg will face a looming labor battle with its main union, the IAM, which is likely to call a strike, no matter what Boeing initially offers, when the contract deadline expires on Sept. 12. Ortberg will need to calibrate the best possible balance between signing a deal that’s overly expensive and preventing a long work stoppage that would further set back the already delayed delivery schedule for the 737 Max and 787 Dreamliner.

Ortberg rose at Rockwell Collins by capturing 787 business via a stunning software innovation

Ortberg grew up in Dubuque, Iowa, son of a dad who worked at tractor maker Deere and a stay-at-home mother of four. He has said in interviews that he loved serving in the Boy Scouts, and that the ethos in the TV show The Wonder Years reminds him of his happy childhood. Today, Ortberg has a waterfront home in West Palm Beach, Fla., and is an ardent golfer. The game, he allows, “keeps you very humble, and only one person can get credit or blame for the result.” He’s a proud University of Iowa Hawkeye. It’s heartwarming, he declares, “when you’re walking the Great Wall of China and see someone with a Hawkeye T-shirt!”

A few years after obtaining a degree in mechanical engineering in 1982, Ortberg joined Rockwell International as a project manager. In 2001, Rockwell split into two publicly traded companies: The aerospace business became Rockwell Collins, and the industrial automation sector emerged as Rockwell Automation. The figure who orchestrated the Rockwell Collins spinoff was Clay Jones, who foresaw that the avionics business could become a much more potent force as an independent company. Ortberg emerged as Jones’s top lieutenant. A former fighter pilot with a big personality, Jones was renowned for getting the troops marching together. In interviews, Ortberg credits two role models with influencing his style of management: Jones and Alan Mulally, who left a top job at Boeing to successfully lead Ford Motor Co. “I’ve never met a better communicator than Clay,” says Ortberg. As for Mulally: “He had a knack for connecting to the employees at Boeing, helping them understand the strategy that drives success. [That’s the] power of getting everyone rowing in the same direction. Alan set [that] tone at the top.”

Ortberg scored a landmark success for Rockwell Collins in the mid-aughts, punching his ticket to the top. Honeywell had long been the largest supplier to Boeing for avionics (the control, display, and other systems that go into the cockpit and that pilots rely on to fly the planes). But in the mid-aughts, Ortberg helped develop avionics that incorporated sophisticated software that made the new systems much more advanced than the previous versions that were far more hardware based. Whereas the old avionics had to be purpose-built for individual aircraft models, and unique to each series, the fresh Rockwell product was much more adaptable to different airplane types. The innovative offering won Rockwell a huge share of the avionics for the 787 Dreamliner, which turned into a big hit for Boeing. Says Spingarn, “That 787 win using advanced software really put Kelly on the map.” He rose to COO of commercial systems in 2010, and upon Jones’s retirement, became CEO of Rockwell Collins in 2013.

Ortberg goes to RTX, but his sojourn is short

Over the next six years, Ortberg roughly doubled Rockwell Collins sales to around $9 billion, in part by making a series of acquisitions, including aerospace communications provider Arinc. Around Thanksgiving of 2019, United Technologies bought Rockwell Collins for $23 billion in equity, four times its valuation when Ortberg took charge. The new owner folded Rockwell’s businesses into its own giant aerospace segment that included franchises acquired from Sundstrand and Goodrich. Ortberg headed the new unit called Collins Aerospace, that comprised 70,000 employees. Its $23 billion in sales made the newly-formed giant the third largest aerospace company in the world after Boeing and Airbus.

But United Technologies’ CEO Greg Hayes had another big move in store. Only seven months after the Rockwell closing, UTX announced that it was merging with military contractor Raytheon in an $86 billion transaction, creating RTX. The deal, which closed in April of 2020, made Collins a much smaller piece of the overall company. Ortberg would have seemed a leading candidate to succeed Hayes, who retired earlier this year. But in a shock to the aerospace world, Ortberg left his post as head of Collins in February of 2020, after less than a year and a half in that job. Thereafter, he briefly took a post advising Hayes, then left RTX in February of 2021, though remaining an RTX director.

It’s interesting that Ortberg’s career intersected with that of Dave Gitlin, now CEO of HVAC maker Carrier Global and a Boeing director. Gitlin had been president of UTX’s aerospace business just prior to the Rockwell acquisition. In the deal, he essentially represented the buyer in combining his segment with Rockwell’s, and Ortberg represented the seller. Gitlin took his name out of the running for the Boeing deal in April. Now, Gitlin’s collaborator in forming the colossus Collins Aerospace will join him on the board, and take on perhaps the biggest challenge in Boeing’s history. The Boeing directors, led by chairman and former Qualcomm CEO Steve Mollenkopf, made what looks like an excellent choice from a narrow range of options, and proved highly creative in tapping someone with all the skills who might have been overlooked since he’d been out of the game for several years. Now Kelly Ortberg is back in the arena, and as he says about golf, it’s going to be a humbling ride, and whatever happens, he’s the one person who’ll get the blame—or the credit.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com